Privacy Disasters: 23andMe, and You, and Our Genetic Data

Or, I was young and foolish in 2013, and now I'm very concerned.

Update (2025-03-24)

23andMe filed for bankruptcy protection and CEO Anne Wojcicki immediately resigned thereafter. In preparation for the inevitable, California’s AG, Rob Bonta issued a consumer alert advising customers to delete their data from the site—though I suspect, that advice may be too little, too late for many.

When I wrote about this originally (in October 2024, I laid out some of the thorny issues and arguments 23andMe might make to keep the data notwithstanding the law. For what it’s worth, 23andMe never provided any details on whether or not they had copies of my data, whether their laboratory maintained my samples or DNA records, or which laboratory processed that data. This may matter as part of any sale of 23andMe’s assets.

AG Bonta has some concrete advice for consumers on how to delete their data, though any legal recourse may be limited — at least in relation to the Genetic Information Privacy Act (GIPA).

To Delete Genetic Data from 23andMe:

Consumers can delete their account and personal information by taking the following steps:

Log into your 23andMe account on their website.

Go to the “Settings” section of your profile.

Scroll to a section labeled “23andMe Data” at the bottom of the page.

Click “View” next to “23andMe Data”

Download your data: If you want a copy of your genetic data for personal storage, choose the option to download it to your device before proceeding.

Scroll to the “Delete Data” section.

Click “Permanently Delete Data.”

Confirm your request: You’ll receive an email from 23andMe; follow the link in the email to confirm your deletion request.

To Destroy Your 23andMe Test Sample:

If you previously opted to have your saliva sample and DNA stored by 23andMe, but want to change that preference, you can do so from your account settings page, under “Preferences.”

To Revoke Permission for Your Genetic Data to be Used for Research:

If you previously consented to 23andMe and third-party researchers to use your genetic data and sample for research, you may withdraw consent from the account settings page, under “Research and Product Consents.”

Under GIPA, California consumers can delete their account and genetic data and have their biological sample destroyed. In addition, GIPA permits California consumers to revoke consent that they provided a genetic testing company to collect, use, and disclose genetic data and to store biological samples after the initial testing has been completed. The CCPA also vests California consumers with the right to delete personal information, which includes genetic data, from businesses that collect personal information from the consumer.

Anyway, re-sharing this for timeliness & information purposes.

There was a big Atlantic piece that came out recently discussing 23andMe’s dire financial troubles and potential stock delisting, and how, absent a miracle or some new funding source to go private, 23andMe was potentially up for sale. (Remember That DNA You Gave 23andMe?)

After shutting down their drug-development unit in August, and several rounds of layoffs, the entire 23andMe board up and quit. So, yeah, the company is not having a good year. Or as CNN notes, they’ve been having “a rough few years”. Cue a potential sale.

Some of you likely see where this is going, but if you don’t, this will be a post about what happens when 15 million people entrust their DNA with a private company, and what could happen if said company does a swirly in the great capitalist toilet. It’s a #privacydisaster on a mass scale, with major and irreversible implications. In short, it’s about the sale of personal data and what you might be able to do about it.

I Am Not Always Good About my Data

Despite all of this (waves arms frantically about the blog), I was once a naïve, overly trusting person. I might even call myself a stupid person when it came to my personal data. For you see, in 2013, I signed up for 23andMe and their Personal Genome Service (PGS), mostly out of a passing curiosity to find out what my DNA could tell me, particularly about heritable diseases.

2013 was a simpler time. I was living in the Bay Area, and people generally liked and trusted tech companies back then. Importantly for this story, I was not really thinking about privacy or data protection in a professional sense, and what concerns I did have were mostly centered around Big Brother-type spying and abuse.

In 2019, after being in the business for a few years, and witnessing countless big tech abuses (including a few by 23andMe), I filed an erasure request. Being in the EU, I reasoned that 23andMe had no legal basis for retaining my DNA data. The company’s privacy statement (both in 2019 and currently) claim that it is entitled legally based on obligations related to their unspecified-in-the-privacy-statement genotyping laboratory partner, LabCorp, to retain genetic data. 23andMe cited to three specific laws/standards:

The Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA);

The CA Business and Professional Code Sec. 1265; and

College of American Pathologists (CAP) laboratory regulations.

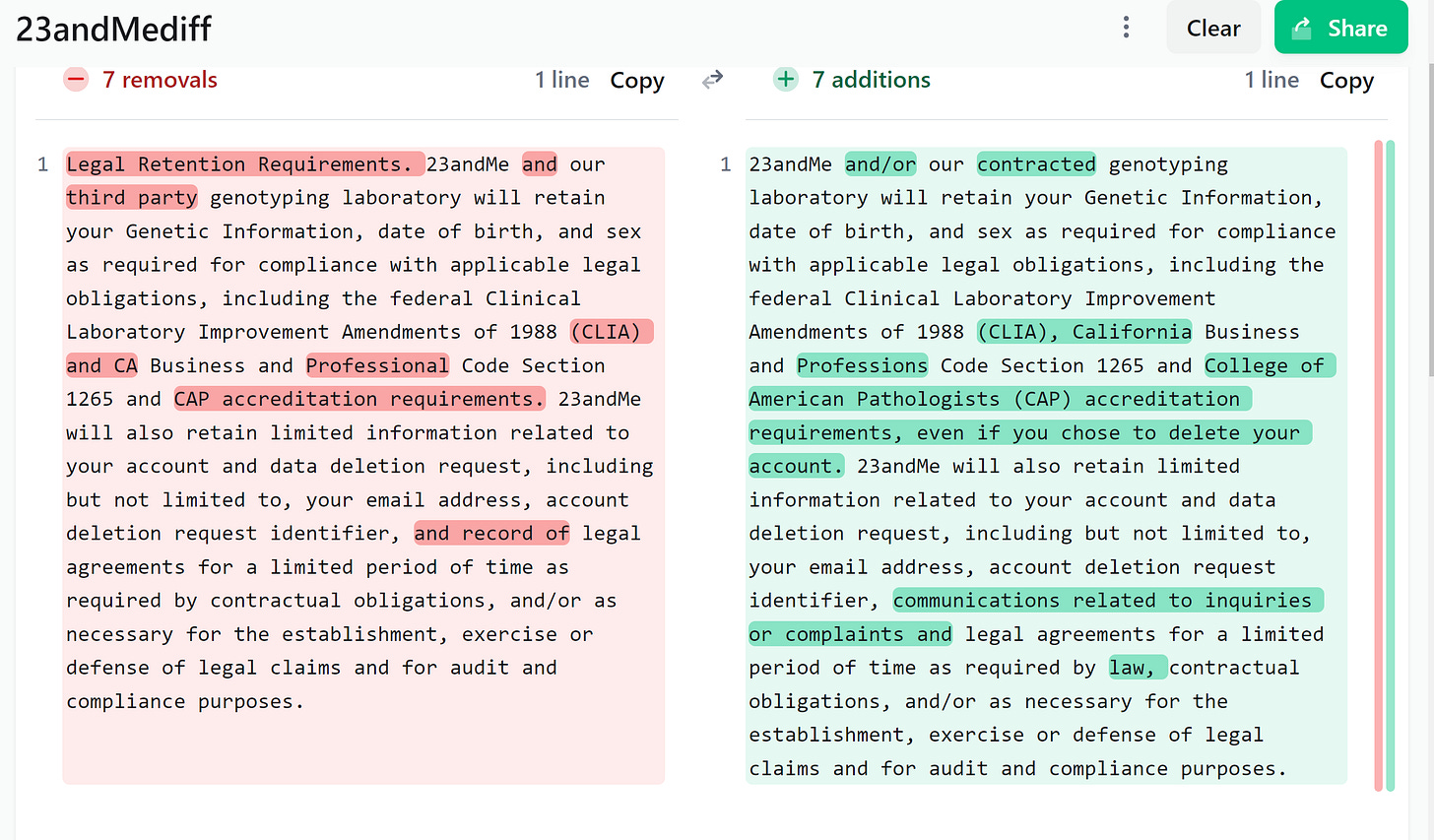

I’ve included a diff of the specific retention & deletion language from their August 2019 statement (which was in force when I deleted my account) compared to the current privacy statement (as of 24 September 2024):

The biggest substantive change is the line that 23andMe and/or the contracted laboratory will retain genetic information even if a user deletes their account.

After the Atlantic piece came out, I wanted to find out more about these laws, 23andMe’s specific legal basis for retaining identifiable genetic data as part of their Personal Genomic Service program, and details about the specific genotyping laboratory who sequenced my DNA in 2013. My goal was to ensure that my deletion request from 2019 had actually worked and 23andMe (as well as anyone who had access to my genetic information) no longer had it.1

This blog post includes the access request letter I sent to 23andMe, and the exceedingly grey area 23andMe might be relying on to retain genetic information and other sensitive health information, as well as whether 23andMe is justified in relying on these laws in the first place.

First, the letter.

On Sept 28, 2024, I sent privacy@23andme.com this letter2:

Hello:

Firstly, I am a resident and citizen of Ireland, and have been residing in Ireland since 2017.

I am seeking information about your fair information processing practices under Article 12 [GDPR] and specific personal data you retain about me (where applicable) under Article 15 GDPR.

On 4/2/2019, I requested the deletion of all data 23andMe had about me, including my genetic data. Your new privacy statement also includes storage of "genetic Information, date of birth, and sex as required for compliance with applicable legal obligations, including the federal Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA), California Business and Professions Code Section 1265 and College of American Pathologists (CAP) accreditation requirements, even if you chose to delete your account."

I have [reviewed] these laws, and cannot find any details as to where a retention requirement for consumer genetic information exists, or why 23andMe the company would be insulated from complying with deletion obligations related to genetic data, for example, under the GDPR, or for non-EU individuals relevant US laws such as the CCPA or the Washington My Health My Data Act. As far as I'm aware, 23andMe is not a genotyping clinical provider.

And so, I'd like to know the following:

1) what specific sections of these respective laws permit 23andMe (the company) to retain genetic information about me, and in [particular, what sections of these laws cover] 23andMe’s retention, storage & sharing obligations;

1a) What specific sections of these laws allow 23andMe to disregard downstream notification obligations to third parties, including genotyping partners, given that this is an explicit obligation under Article 19 GDPR;

2) what specific sections of these respective laws permit your genotyping laboratory [partner] to retain this information, particularly, details around retention, storage & sharing obligations;

(In essence, these questions are asking for more details on your specific legal obligations, beyond blindly citing to random laws that exist [that] vaguely deal with health).

3) which genotyping clinical partner(s) you were using on or around December 2013 (so I can follow up with them directly to inquire about deleting my genetic information and records, and their retention periods and other matters);

4) how these clinical standards obligations override the GDPR and other equally stringent [data protection laws], and what assessments have been undertaken to come to this conclusion;

5) whether genetic data will be sold or transferred to another entity in the event that 23andMe (or it's genotyping partner(s) is/are liquidated, sold, acquired, or merged, etc;

6) what remaining information you have retained from 2013 to the date of this email, including, but not limited to any and all records about me, my account, my genetic data, relatives information, correspondence, website activity, etc., and the retention period for continued storage of this information. [trimmed the paste of the privacy notice —CL]

7) what information/types of information about me, particularly genetic information and other health information, have already been sold, shared, or otherwise made available to third parties, business partners, clinical research partners, hospitals, commercial providers, etc. Effectively, I'm seeking a list of your subprocessors and joint/co-controllers who may have my genetic and health information, notwithstanding my [2019] Article 17 GDPR request.

8) what steps are being taken to secure my genetic information and personal information [that] 23andMe continues to retain, given the recent data breaches.

Thank you in advance. I expect a timely response, including details on whether an extension is necessary within 30 days.

What Do These Laws Cover?

Recall that 23andMe relies on three laws or guidance regulations to support their legal basis for processing and retaining genetic information as part of their Personal Genetic Service (PGS) program:

The Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA);

College of American Pathologists (CAP) laboratory regulations; and

The CLIA sets standards and certification obligations for clinical laboratories, including those that perform testing, including genetic sequencing. According to 42 CFR § 493.1105, the CLIA sets minimum retention periods for laboratories storing specimens—most range between two and ten years. However, there’s nothing in the law that mandates indefinite retention, and one thing that would be good to know is whether 23andMe (or its clinical partners) are retaining genetic information for longer than these minimums, and their reasons for doing so.

Under the 42 CFR § 493.2 , laboratories are well-defined as:

a facility for the biological, microbiological, … pathological, or other examination of materials derived from the human body for the purpose of providing information for the diagnosis, prevention, or treatment of any disease …. of, human beings. … Facilities only collecting or preparing specimens (or both) or only serving as a mailing service and not performing testing are not considered laboratories.”

The College of American Pathologists (CAP) also has a retention schedule for laboratory records and materials. The CAP is responsible for accrediting approved laboratories, and its retention schedule is similar to, though a bit more generous than the CLIA. On page 3 of the ‘Policy PP. Minimum Period of Retention of Laboratory Records and Materials’, retention of Cytogenetic specimens and cultures is ‘until release of the final report’, with the final report being held for up to 10 or 20 years for neoplastic and constitutional disorders, respectively. The specimen and genetic data itself should not be retained. Importantly, the CAP guidance is arguably not a law as such, so much as an industry certification, but I’m happy to be corrected on this issue.

It’s unclear to me then how the CAP guidance or the CLIA apply to non-clinical consumer DNA testing services like 23andMe, as these services do not provide “information for the diagnosis, prevention, or treatment of any disease”. Lest anyone think this is me speculating here, 23andMe directly state as much on their 23andMe for Healthcare Professionals site. In tiny 8-point font, 23andMe note that their tests are “not intended to tell you anything about your current state of health, or to be used to make medical decisions, including whether or not you should take a medication, how much of a medication you should take, or determine any treatment,” and that the results are “not intended to diagnose any disease.”3 Hmmm…

Finally, there’s the California Business & Professional Code, BPC § 1265. This law covers licensing for clinical laboratories based in California, and relies on the CLIA standards and obligations, including the CLIA’s definition of laboratories.

Is 23andMe a CLIA?

So, I’ve laid out the law, and if you’ve made it this far, you might be wondering: is 23andMe even a CLIA?

Here’s the thing: As far as I’ve been able to tell, the answer is probably not, or at least, not federally anymore.

I chatted with a few experts on clinical laboratory processes, and one of them very helpfully pointed me in the direction of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Quality, Certification and Oversight Reports (QCOR) and specifically, its clinical laboratory lookup page. There’s absolutely no record for 23andMe I was able to find. What’s weird, is a registration for 23andMe in two state registries—California and New York (PFI: 9371) exists. California’s record hasn’t been updated since April 2020 though, and no technical designation exists. It just shows up in results. My friend noted that this isn’t unusual as many CLIAs prioritize CA and NY registrations as they are distinct enough from the federal standard and actually have enforcement.

Importantly, 23andMe themselves are not exactly clear about their CLIA status. Here’s some choice bits from their own documentation, emphasis mine:

“23andMe laboratory testing is done in U.S. laboratories certified to meet CLIA (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988) standards, including qualifications for individuals performing testing and other standards to ensure the accuracy and reliability of results ...” (23andMe for Healthcare Professionals)

“All saliva samples are processed in CLIA-certified and CAP-accredited labs.” (How does 23andMe Work)

“We work with third-party companies to provide users with services on behalf of 23andMe, ... Specifically, our contracted lab has access to users’ DNA samples and limited user information for processing purposes. Under the [CLIA of 1988], 23andMe is required to provide the laboratory with the customer’s sex and date of birth. No other Registration Information (such as name, address, email, phone number or other contact information) is provided to the laboratory. Samples and data are otherwise identifiable only by the unique barcode that is used to register a saliva collection kit tube.” (23andMe Guide for Law Enforcement)

But see:

“As part of our methodology, our CLIA-certified lab extracts DNA from cells in your saliva sample. Then the lab processes the DNA on a genotyping chip that reads hundreds of thousands of variants in your genome. (The Science Behind 23andMe)

So are they? Aren’t they? I don’t know. And 23andMe have yet to respond to two separate requests for information. If 23andMe no longer maintains a CLIA laboratory, it’s hard to see how the CLIA applies to them, or can be used to justify storage of genetic information (beyond, perhaps for a few years).4

Complicating this whole mess is the fact that according to Wikipedia, “[t]he US currently does not have well-defined federal regulations regarding the ownership and utilization of physical human tissue specimens, their derivatives, as well as the biological information they contain.”5 Importantly, the current position of some bioethicists is that patients who have consented to have their diagnostic specimens collected have abandoned those specimens, and thus have no ownership rights, assuming varying degrees of ‘deidentifiability’. If that’s the prevailing view of the industry, it should give everyone serious pause.

Despite claims to the contrary (and as 23andMe’s breach of genetic data has shown), it is possible to re-identify ostensibly de-identified genetic data with other information (such as those on genealogy websites) and use it for nefarious purposes. And while laws in the US like the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act exist to prohibit employers and insurers from using genetic information to discriminate against individuals based on their data, numerous loopholes and exceptions exist, including the purchase of ‘aggregate’ genetic information.

By all appearances, it seems like 23andMe may be leaning into these ambiguities to potentially ignore data protection laws. Regardless of the reason, this approach does not fill me with joy regarding 23andMe’s data governance processes, or plans if the company cannot remain solvent. Sure, there might be prohibitions on the sale of genetic data to employers and insurers, but not, for example, to data brokers, law enforcement personnel, AI model developers, tech companies and any number of other sundry opportunists.

The bottom line is, until I get confirmation that they are not, in fact storing anything of mine (bar my deletion and access requests), I’m going to keep hammering home that nobody should be entrusting this company with their genetic material, and if you, as I, made the choice to do so in the past, now is the time to at least proactively demand to have that data deleted. Importantly, for those in the US, I urge you to contact your elected representatives and senators to probe for more information, because absent making noise about this issue, I suspect the status quo approach will be whatever favors 23andMe — and not what is best for you or I.

Additionally, 23andMe also have specific consents that discuss the storage of genetic data in biobanks (deidentified) and for their research program (which includes identifiable information about participants). Biobanking consents do not expire, unless consent is withdrawn. Individual research consents can be withdrawn, but details about retention are non-existent.

Hi 23andMe legal team! Please note that I have made a few minor edits indicated in brackets to this letter, mostly for clarity purposes and fixing inconsistencies in the 23andMe name. I wrote the original on my phone, with only half a cup of coffee, so it wasn’t expertly proofread. Substantively, nothing has been altered.

This was most likely added in response to an FDA warning letter issued against 23andMe in 2013. The FDA warning letter 404s as records are no longer kept online before 2019, but here’s the citation: US Food and Drug Administration. Warning Letter. To Ann Wojcicki, CEO. 23andMe, Inc. 22 Nov 2013. See also: Rachel A. Hardy, MD, “CLIA-Regulated Laboratories vs. 23andMe - an Apples-to-Oranges Comparison”, at: https://www.ncraf.org/index.php?option=com_dailyplanetblog&view=entry&year=2014&month=06&day=03&id=3:clia-regulated-laboratories-vs-23andme

I will profess that I am not a clinical researcher and this is not my area of expertise. It’s entirely possible that buried in the bowels of 42 CFR that there’s some explicit retention period for entities like 23andMe, but I have not found it. If you are an expert and would like to set me straight, please ping me at carey@priva.cat.

FWIW, there was an announcement in 2008 that 23andMe was using LabCorp to conduct direct-to-consumer DNA testing for the company. Whether they are still using LabCorp 16 years later is not completely known, but I suspect that they are.

Wikipedia’s entry for CLIA is remarkably extensive, and includes a number of citations to bioethicist opinions and research. It’s worth a view.

“The bottom line is, until I get confirmation that they are not, in fact storing anything of mine (bar my deletion and access requests), I’m going to keep hammering home that nobody should be entrusting this company with their genetic material, and if you, as I, made the choice to do so in the past, now is the time to at least proactively demand to have that data deleted.”, you are not being strong enough in your request here. People should not be entrusting ANY private company with their genetic material. The mistake you made so many years back is one that others have continued to make and revolves around trust and curiosity, both being roots of the failures that continue to put people’s information in so many equally important areas at great risk. 23andMe is simply the latest fiasco, and even if they had not gone bankrupt it was not a good idea to entrust this most valuable information about yourself to them. For all the good reasons people come up with for using these services, the intangible risks that inevitably follow and are foreseeable to privacy practitioners, seem to escape their field of vision. It’s unfortunate, but it’s also why we find the state of privacy and abuse of people’s data by so many entities at such an all-time high.