Remembering Joi (July 2020 - December 2025)

Remembering our most chill fur baby, who died very suddenly.

I’ve had a cat since I was eight.

And for the past thirteen years, I’ve bottle-fed tiny day old babies, fostered countless furry teenagers, been a halfway house for pregnant mommas, and an old-age home for elderly moggies with lots of purrs left to give. During the pandemic, our house offered shelter for around 100 cats (across a four year period), almost all of which found forever homes. Some came for days, others weeks or months. Some of them, intentionally or otherwise, never left.

When Joi, his brother Max, and their siblings, Ruth, and Jung came to us in July 2020, they were a few weeks old. As we’d recently had to say goodbye to another cat, Molly, this crew came to us at the right time. The entire litter exuded calmness. They were all so friendly, so agreeable, and so eager to love, so we dubbed them the ‘Therapy Cats’.

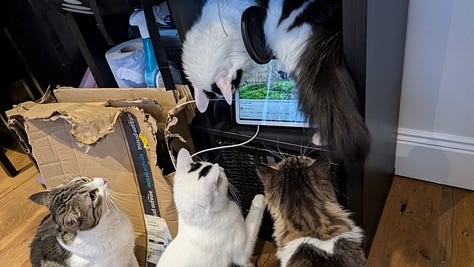

Of the four, Joi was by far, the most friendly and easy-going of the bunch. I honestly should have named him Buddha because this cat was one with the universe. He was patient with nearly every kitten and cat we introduced, got along with dogs, greeted every guest (he and Leroy were always part of the welcoming committee), and even tolerated screamy children. Joi was literally the only cat who got along with our cantankerous old lady, Daisy, and one of the few who our mentally-challenged Octopus had enough object permanence to remember wasn’t a threat.

And the purring! This cat was constantly running his motor. If you picked him up, he’d purr, relaxed, with slow eye-blinks of trust. He purred loudly for belly rubs. He’d purr when he got his nails clipped, when getting flea treatment, or even taking medicine. He purred when he had to go to the vet. He purred at the vet, to the point where they couldn’t hear his heartbeat over the purring. When the cats moved from Ireland to the Netherlands in November, the cat “transpawters” even commented that Joi purred most of the way.

Joi was the embodiment of bliss, in cat form.

When I had a shit day, he was there. Probably for food or treats, but I like to believe that it was also because he knew I needed comfort. He loved to lay on my chest, licking my nose, and gently head-butting for affection. He had an intense, focused gaze, like he was trying to focus on understand what the agitated gorilla pig wanted or was saying. He’d take it all in, with his perfect green, marble-like eyes gazing into yours, unblinking, and I could stare at him forever.

Outside of occasionally singing the song of his people at 3am, he rarely meowed or vocalized. And beyond a brief period where he enjoyed free-peeing on papers to our annoyance (we dubbed him ‘Pee-iere’ during that trying period), he had no behavior issues. He was silent and low maintenance. He was happy to nap in the window, lay on your legs, and occasionally chase a laser pointer if offered. He loved to wrestle and play with Max and the other cats, though his play sessions weren’t as common as he grew up.

He was an absolute fiend for Churu though. I mean, if anything got Joi going it was Churu. He would take down anyone that got in the way of his sweet, sweet tube action. The only time he actually swiped at me (accidentally) was when I had an open tube packet and I wasn’t moving fast enough.

Three days ago (December 15), he was fine, chilling as usual, but the next day, I noticed a change: he was sleeping more than usual in the same spot (it’s hard to tell ‘more than usual’ compared to ‘standard cat length’ given that cats sleep for 18 hours a day). He camped out the entire day on a shelf in my office, and it wasn’t until the evening when I realized he hadn’t really gone downstairs at all to eat or use the litter box. But I didn’t think too much of it—Joi had a tendency to jump from things and had sprained his paw a few times in the past. He’d usually sleep it off, recover in a day or two and go back to being himself.

In the evening, I gently prodded him, and finally took him downstairs, but he wouldn’t eat or drink. He moved on his own, but seemed unsteady. I realized something was very wrong. I called the vet first thing in the morning (December 16) and got him in. They did a few tests, and then reported that there was little they could do—I would need to take him to the emergency vet hospital in Nieuwegein. He was going into septic shock.

We raced him to the vet hospital and waited. The prognosis was poor because he was septic, the likely cause being pyothorax—pus in the lungs from an infection. The vet didn’t know the root cause of the infection, but speculated that it could have been through a bite (from one of our other cats), or a migrating foreign body. Still, they had some hope. He was a youngish cat, didn’t have any pre-existing illnesses, and seemed like a fighter. Still, time was not on our side.

The vet hospital was good about keeping us updated, but suggested we go home for the evening and they would call. To their credit, they (Evidensia Dierenzeikenhuis) called every few hours to give us updates.

His status teetered like a see-saw: first, it was getting worse, then slightly better. Then he was stable, but round midnight, they called again for the last time. Joi had stopped breathing. The fluid was too much for his little body to fight off, and he was drowning in it. They asked if we wanted to come down—they could keep him alive by ventilation, but he was suffering. There was nothing they could meaningfully do beyond keeping the body going just a little longer for us to get there. I knew it would take us thirty minutes to make it to the hospital, and that it wasn’t fair to him, to wait and suffer just so we could say goodbye.

The next morning, we biked along the canal to see him. It was a cool, crisp winter day, and the bike path took us along the Rhine most of the way. I imagined what it would be like to bike in the summer months. How I’d wanted to take Joi and the other cats on bike rides like this when the weather improved. And how I wouldn’t be able to take him.

When we got to the hospital, they asked if we wanted the body, or we wanted to see him, to say goodbye. I assented, and they took David and I to a room off to the side of the hospital. I remember there were diagrams of animal organs on the wall, but this was bigger than a normal veterinary office. The nurse brought his little body in, wrapped snugly in a blanket. He looked like he was sleeping.

Cats always look like they’re sleeping. I like to pretend they’re dreaming of mice or treats, or other happy things. But I know they’re gone. When I’ve had to say goodbye to cats in the past, I was always there with them, going back to the first cat I had, Patches. I never wanted my cats to die alone. I was there with Neko when she slipped away, dying after a prolonged seizure as I raced her to the hospital. I was there for Molly, and most recently for Daisy, when the lethal injections of sodium pentobarbitol were administered. I was present over the years as the vets had to put down half a dozen frail, week-old kittens that came into our care with defects or irreparable illnesses, whose eyes never opened to see the world.

But I wasn’t there with Joi, and I hate myself for this. He died without us by his side. I had made the selfish decision to go home, hoping he would improve, rather than be there for him, and he died without us, in a strange, sterile place. And I hadn’t paid as much attention as I should have to his behavior, to the signs of lethargy and weakness earlier, which could have saved him had I taken him in to the vet the previous day.

He was a wonderful, sweet, zen boy, and I’m going to miss him so much. I’m going to miss his calmness, his deep looks, and the ferocity he had when it came to treats. I’m going to miss the licks on the nose in the morning, all the biscuits baked in the evening, and his shadowboxing with Max.

Death never gets easier, even though we like to pretend it might if we see enough of it. And with pets, it feels like death comes so much more often. We have less time with them, and yet when they’re gone, we still feel the heartache. For me, I love these cats more than I love most people, and frankly, I’m grieving his death harder than I have for most human relations I’ve lost.

He brought so much unconditional joy to our lives. Maybe he really was given the right name, after all.

Thank you for sharing, Cary. I know it’s hard now but you were so lucky to have Joi in your life. He was clearly lucky to have you and your husbot. I appreciate how you celebrated your time with him in this post. Sending you all lots of love

I’m so sorry Cary. I feel for all of you, and can relate to, for each part of your pain.