Welcome to the Splinternet

Or how the European Data Protection Board, the Court of Justice for the EU and Max Schrems might be killing the internet.

Well, it looks like the long-awaited Irish Data Protection Commission decision against Meta has finally dropped. The DPC imposed a €1.2B ($1.3 B USD) fine on Meta, or about 1% of the social media giant’s worldwide turnover for 2022.1 The DPC also ordered Meta to cease transfers of data outside of Europe within five months, and to return or delete all EU/EEA personal data transferred unlawfully to Meta, Inc. by no later than November 2023.

Obviously, this impacts Meta, but it’s important to understand how this decision will likely have knock-on effects to the internet and everyone on the internet as well. This post is my attempt at explaining how we got here, the implications of this decision, and why there are no simple answers.

Tl;Dr:

I read a 222-page decision so you didn’t have to. I also summarized relevant legal bits and share details on how we got into this mess in the first place. [Parts 1 & 2]

Due to the realities of the US surveillance state and the absolutist posture of the EU Court of Justice & EU regulators, there are currently no meaningful or scalable legal or technical solutions available to lawfully share data with US companies. That leaves political solutions, whose prospects also don’t look great. [Part 3]

This decision won’t just fall on big tech, it will impact others, including users. Now that one regulator has acted, more will likely follow. [Part 4]

Due to the depth and breadth of this decision and a likely increase in post-Meta enforcement actions against others, I worry that this lead to a fragmented internet, aka, a Splinternet, as companies nope out of the EU rather than risk fines or orders to stop processing data. [Part 5]

I wish I had better suggestions on how to fix this mess, but I don’t. Sorry. I do have some amusing and informative footnotes though.

Part 1: A Short Summary of the Decision

The decision itself wasn’t much a shock to folks who have been paying attention as it is largely an implements an earlier binding determination made by the European Data Protection Board (EDPB), the oversight body of all data protection authorities in the EU. While the details of the earlier EDPB ruling were not published before, most privacy pros expected it would be severe. The DPC reached five conclusions:

Meta Ireland infringed the GDPR2 when it continued to transfer personal data of EU/EEA data subjects to Meta, Inc. in the USA, following the July 2020 judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) invalidating such transfers (the Schrems II decision);3

Meta Ireland could not and cannot now rely on any of the special legal mechanisms or exceptions available under the transfer rules of the GDPR (known as ‘Chapter V Transfers’). This is because none of the available legal mechanisms provide ‘effective safeguards’ against US governmental abuse as they cannot entirely eliminate the risk of disproportionate government surveillance;4

Because Meta Ireland violated the GDPR and has no effective legal exceptions available, Meta Ireland must cease any future data transfers to Meta, Inc. within five months (~ October 12, 2023);

Meta Ireland must also bring its processing operations into compliance with Chapter V, by ceasing any current processing in the US, including storage of personal data collected after the Schrems II decision. In practice, this means returning data to the EU or deleting the data of EU/EEA data subjects;

Meta Ireland must pay an administrative fine in the amount of €1.2 billion ($1.3 billion) in respect to these findings.

Part 2: How Did We Get Here?

If you can believe it, this whole thing kicked off nearly ten years ago on 25 June 2013, when Max Schrems filed his first complaint with the DPC against Meta (then Facebook) Ireland regarding Facebook Ireland’s transfer of EU/EEA data to Facebook, Inc. in the US (Schrems I). A whole bunch of legal things happened between 2013-2020, including the invalidation of an earlier adequacy agreement between the EU and US by the CJEU. Unfortunately this post is already long enough, and I really don't have time to summarize it all.5

In its July 2020 judgment (Schrems II), the CJEU found that the US government’s broad use of surveillance against non-US individuals was disproportionate; that the new framework in place between the EU and US (the ‘EU-US Privacy Shield’) did not provide “essentially equivalent” levels of protection for individuals (data subjects) in the EU; that the Privacy Shield framework lacked any sort of effective oversight and offered no meaningful method of redress to affected EU data subjects; and that Facebook could not safeguard data subjects from the risk of government surveillance based on that framework.

In August 2020, a few weeks after the decision, the DPC opened an investigation against Meta. Almost two years later, in July 2022, the Data Protection Commissioner issued a decision which found (amongst many things) that Facebook’s data transfers were carried out in breach of the GDPR, and therefore should be suspended.

Due to the nature of the GDPR, and the fact that Facebook/Meta operates not just in Ireland, but throughout the EU, the DPC’s draft decision was sent to the other data protection authorities for review and agreement. Let’s just say that the draft decision did not go over well. While everybody agreed that Meta violated the law and future transfers should be suspended, some regulators found that the DPC was too lenient on Meta, both because it did not require the deletion/return of already-processed data, and because no administrative fine was imposed. On this latter point, I completely agree.6

Since the regulators disagreed, that meant that the whole thing had to be settled by the EDPB. The EDPB issued a summary of its binding determination (but not the decision itself) April 2023, and even that was pretty rough.7 Today’s decision implements those findings. Both the DPC and the EDPB decisions can be found here.

Part 3: Breaking Down the Decision & What it Means

Firstly, I legitimately do not care about the fine. Fines are boring, and the most I’ll say about it is that it is the largest GDPR fine to date. It’s still a fraction of a Metaverse, and nowhere close to as high as it could have been. I also believe (along with a few of my esteemed colleagues) that nothing will happen immediately because Meta will litigate this decision for years. Additionally, a proposed new Privacy Shield (the EU-US Data Privacy Framework (DPF) and new US Executive Order (EO 14086) may also help delay the most severe effects of this decision for most organizations.8

But let’s say I’m wrong. Let’s say Meta doesn’t appeal, or they exhaust their appeals quickly and the European Commission doesn’t approve the DPF.9 What happens if this decision gets applied?

Facebook Must Cease Future Transfers

It’s important to note that this is not the first time a regulator has imposed a sweeping ban on future data processing. CNIL (the French DPA) did it against Clearview AI in 2021, and the Italian regulator, the Garante, briefly issued a no-processing order against OpenAI in March 2023. Smaller controllers have also been ordered to stop processing EU personal data via Google Analytics.

But here’s the thing — with the exception of OpenAI (whose processing restriction was lifted before it had a meaningful effect), there has been very little user impact from these processing restrictions. If I’m a business and can’t use Google Analytics, that sucks for me and it eventually might suck for Google. But I can still conduct my business online even if I have slightly less effective ad targeting. Users of the internet won’t be impacted at all. Even if those services get nuked, we can keep visiting websites, accessing information, communicating with our friends, loved ones, conducting business & buying goods online.

Unlike the above, forcing Meta to stop processing EU data doesn’t just hurt Facebook/Meta. As of February 2023, Facebook had over 255 million monthly active users in the EU, and almost 3 billion monthly users worldwide.10 Some of these people rely on Facebook as their social glue, a service which directly connects them (especially Messenger & WhatsApp) to friends, family, loved ones, businesses & social supports.

In a world where data transfers are banned, that option no longer exists because the communication itself is processing. This is because almost any thing that can be done with or to personal data is considered processing as far as the GDPR is concerned.11 In short, every time I as an EU user post to a group or channel, engage with a business, view a page or post, use Messenger … Meta is processing information about me. And because the internet is global and as the name implies, interconnected, the chance that this processing goes to the US is almost 100%. Which means Facebook/Meta are also transferring my data outside of the EU/EEA.

Now you might argue that Meta could solve this problem by doing better at privacy. And while I am no defender of Meta and think they’ve been bad at all of this for over a decade, there is literally nothing that Meta can do to comply in this case. Literally. Nothing.

There Are No Legal Solutions to This Problem

Fundamentally, the grievance of the EU is a political one. The EU is big mad about the US having garbage privacy laws. I agree. The US does have garbage privacy laws, and they should fix them.

The US gives wide latitude to, and maintains almost zero oversight of its national security and domestic law enforcement apparatus (i.e., NSA, CIA, FBI, local law enforcement). The US refuses to recognize fundamental human rights to privacy and data protection, and has no meaningful federal law on the subject. Instead, it applies a piecemeal approach to privacy based on judicial decisions, state laws, and narrow, sectoral legislation like the HIPAA and the FCRA. It also restricts most of these shallow protections to US citizens. According to a 2007 Privacy International study, the US is also recognized as an “endemic surveillance society’ which doesn’t help:

In the Schrems II decision, the Court ultimately found that the entire US privacy framework was inadequate. Short of getting Congress to act (or arguably, a beefier Executive Order which might be legally impossible), there’s not much that can be done to fix this mess.12 There is also nothing meaningful that Meta (or any organization) can do from a legal perspective to stop the US Government from demanding information, no matter how many privacy notices it drafts, contracts it signs, or promises it makes.13 As the DPC noted, “the 2021 SCCs [the contracts Meta relied upon] cannot compensate for the inadequacies in the level of protection afforded by US law.” There’s two reasons for this:

A contract only binds the parties who sign it. The US government isn’t a party.

A contract will never be stronger than a bunch of guys with guns who have the power to lock you in jail for non-compliance.14

In addition to torpedoing the contractual approach, the DPC also concluded that there were no other effective remedies or legal controls (including the special transfer ‘exceptions’ known as derogations)15 that would magically make transfers to the US legal because there’s always going to be a risk that the guys with guns (aka, the US government) will violate EU human rights.

To be blunt, Meta, legally speaking is hosed.

There Are No (Real) Technical Solutions Either

Now, many well-meaning sorts have argued that Meta simply didn’t try hard enough at a technical level to limit or restrict access to EU personal data — that this was due to their incompetence/malfeasance/intentional non-compliance with the law. And, having worked there for a year and change, I’ll agree that they probably missed the mark by quite a bit. But even if Meta had done everything within their power as required under the GDPR, given ‘the state of the art, the costs of implementation and the nature, scope, context and purposes’ of the processing, and the fact that nobody can meet the impossible standard of avoiding all risk, I don’t think anything they could have done technically-speaking would have mattered.

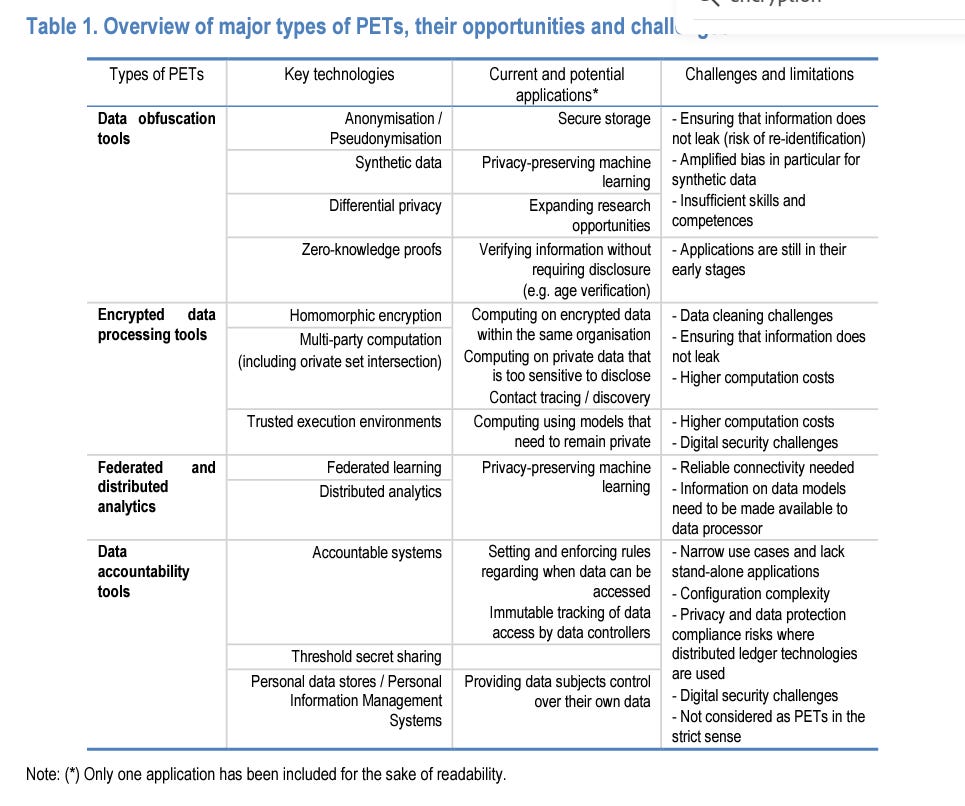

Regulators, as I have noted before, are generalists, not technical experts. They rarely keep apace of the current state of the art when it comes to technology in general, much less privacy-enhancing technologies. And the current state of the art for most Privtech is still quite nascent, limited, costly & difficult to implement. Let’s consider some of the options available under encryption, which is one of the few mechanisms specifically called out as GDPR-approved ‘technical measures’.16

End-to-end encryption (E2EE), which is what Meta uses in WhatsApp, suffers challenges around functionality, recovery, and effectiveness. It’s an exercise in trade-offs. Weaker E2EE (e.g., where keys (or an encrypted copy of the key) are stored centrally) might allow more feature-rich products and the possibility to recover account information, but it’s effectively worthless from a data protection standpoint & doesn’t overcome the risks identified in the DPC or CJEU decisions.

More robust E2EE by contrast, where keys are stored only with the users, mean more security, but often less features (it’s hard to fix bugs or build in data-enhancing services when you can’t see what’s breaking or what data is there). They also have trade-offs when it comes to recovery of data when things go wrong. Should a user lose their key or device (or have it confiscated), forget to write down their recovery key, or die, that’s it, the data is gone.

This isn’t a bad thing necessarily, but it puts a lot of onus on users who may not know, care, or be technically competent enough to manage those keys.17 And even E2EE may cease to be a viable option if the EU implements so-called “Chat Control” client-side scanning features on devices to combat the spread of illegal materials and child sexual abuse material.18

Other more exotic privacy-enhancing technologies also suffer from limitations which make application-at-scale particularly challenging. According to an excellent OECD report on privacy-enhancing technologies, most difficult to implement outside of a handful of niche use-cases.

To be fair, some of these tools might eventually work for some types of processing, but not others. For example, encrypted data processing mechanisms such as homomorphic encryption and multi-party computation, might be options — Meta researchers have proposed a mechanism, for example using homomorphic encryption, to ‘read’ encrypted WhatsApp messages and infer what ads should be shown in such a way that neither Meta, Inc. nor the US government can see the contents of the data.19

That is of course, where we need to be headed. But right now, we’re simply not there yet. And even if we do get cost and complexity down, and improve on use cases and implementation, there may be other factors (like poor network connectivity and use of older devices) which make wide-scale adoption difficult, especially outside of the Northern Hemisphere.

Facebook Must Delete the Data it Currently Processes and Stores

Since neither I nor the regulators have a clear idea as to how exactly Meta can ‘return’ data to the EU in this case, let’s focus instead on the far more likely result: deletion. Like the underlying transfer ban, deletion will primarily harm users more than Meta itself.

Come November, EU/EEA users risk losing their posts, photos, videos, and messages on Facebook. Small businesses who use Facebook to reach their customers will also lose a valuable communications channel. Now, you may personally think Facebook/Meta is an evil data vampire who offers a product with zero redeeming social value, but millions of people in the EU feel differently. Being empathetic to those concerns doesn’t make me a corporate shill — it makes me a person.

Wait, Can’t They Just Store Data In Ireland?

The short answer is, no. Based on how the US’s overbroad legal regime works, Meta Ireland remains subject to US laws so long as Meta Inc. maintains any degree of “possession, custody, or control” of the data Meta Ireland keeps (see FN 13).

It turns out, just sticking data in an EU data center doesn’t cut it because data moves and the internet interconnects everything. Now, some tech companies (notably Google and Microsoft), have been working for years on ways to ensure data sovereignty and localization via technical and legal means. This includes creating EU data enclaves and sovereign cloud solutions, as well as engaging with trusted EU-based third parties to handle the day-to-day management of systems and services, free of US parent oversight and presumably free of US government reach. While these approaches seem like the perfect solution, the reality is far more fractally complex.

Let’s take an example. Say you’re an EU business who wants to run Microsoft Office365 in the EU. Microsoft has numerous data centers in the EU (including Ireland), but currently, at least some data (logs, telemetry data, source code, technical support, analytics, etc.) is shared with data centers located all around the world — including America. To do sovereignty effectively, Microsoft would not only need to ensure that it’s not sharing data directly with an entity located in the US, but also that absolutely no EU personal data gets back to servers located outside of the EU in any way.

That means:

A separate company must be established. It must be entirely independent, and strict agreements will likely need to be in place to ensure that nothing is shared between the two companies (what sometimes is known as a ‘Chinese Wall’). Let’s call the new entity Tfosorcim Ireland.

A separate code repository needs to be developed. Any integrations, data stores or other shared services that currently exist must be separated. After all, if you have code directing where data should be stored, and the programmer accidentally defaults to the US, it’s game over.

Strict access controls must be in place making it both logically and physically impossible for Microsoft Inc. personnel to access Tfosorcim Ireland data, code, logs, etc.

Since Microsoft Inc. won’t have sight of Tfosorcim Ireland’s code, they won’t be able to (easily) collaborate on features, improvements, or security updates. Products will drift. Information sharing will grind to a halt.

As a wholly separate entity, Tfosorcim Ireland cannot rely on Microsoft Inc. for things like operational or technical support, information security & network support, legal compliance, or anything that might in any way touch customer or employee data. The moment EU personal data gets shared (even things like metadata and log data) is the moment that the US government can argue that Tfosorcim Ireland is merely a subsidiary of Microsoft.

It turns out, making this work in a way that doesn’t absolutely degrade the user experience or cost absolute truckloads of money (increasing user cost) is really, really hard.

And here, we’re talking about doing this for a company with a $2.3 trillion dollar market cap. Now Imagine trying to do this as a small or medium-sized startup.

Part 4: This Isn’t Just About Meta & Big Tech

Anyone who thinks that this will only apply to Meta (or big tech) is kidding themselves. The sweeping breadth of this decision, erosion of any valid legal framework for transfers, and imposition of compliance burdens that are effectively impossible to meet means that any US organization doing business with people in the EU should reevaluate their life choices. At the very least, they need to sit down with their data protection officer and/or legal teams and have a good long think (or cry) about what to do next. Probably with a strong drink at the ready.

This decision will lead to future action against US companies that engage with people in the EU. The DPC said as much in the Meta decision:

[T]he analysis in this Decision exposes a situation whereby any internet platform falling within the definition of an electronic communications service provider subject to the FISA 702 PRISM programme may equally fall foul of the requirements of Charter V GDPR and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights regarding their transfers of personal data to the USA (Sec. 10.11).

The only question up for debate is how quickly regulators will act, and if they’ll act before political will shifts. I’ve observed that regulators tend to follow a pattern - there’s lots of regulatory wait-and-see and then one regulator moves and the dam breaks. We saw this with the flood of decisions against EU companies’ use of Google Analytics after Austria kicked things off in December 2021, and a similar series of cases against Clearview AI in 2022.

As I noted earlier, the GDPR doesn’t care whether you’re a massive multinational or a small struggling startup. The GDPR (unlike most US privacy laws) applies to any organization processing data in, or about people in the EU.

Part 5: Welcome to the Splinternet

When John Perry Barlow wrote ‘A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace’ in 1996, his dream was of a new, promising future — one of open communication and interconnectivity, free of governmental interference, onerous rules, and borders. Despite the ideals espoused in Barlow’s words, rules & laws have been established, and governments have interfered by creating various “methods of enforcement”.

Still, most countries (bar totalitarian states like China, Russia, & Iran) had not gone as far as erecting meaningful digital borders. Information has (mostly) continued to flow freely across a shared internet. I worry that this may not be the case for much longer. In a push to protect some rights (privacy & data protection in this case), I worry that the EU is unknowingly sacrificing others and sliding towards a world where there is no longer a single connected internet but many isolated, splintered ones.20

By assuming that all risks are equally likely and that nothing short of absolute perfection will suffice, I worry that we’re letting privacy absolutism and legal thinking premised on hopes, not reality, drown out everything else. As Eduardo Ustaran noted in a recent LinkedIn discussion, the only way to transfer data in a post-Meta world requires organizations to do the impossible: fully eliminate risk.

Short of the impossible, or the almost-impossible — i.e., Congress actually passing an “essentially equivalent” privacy law, or everyone taking a step back and really grokking how complicated all this shit is — I don’t see much in the way of positive outcomes here.

I worry that many companies may decide in the intervening period of uncertainty and impossible competing legal regimes to simply stop engaging with the EU altogether, as some did when the GDPR took effect in 2018. I’m reminded of all the banners I continue to see on US news sites and online shops with something equivalent to 'Sorry, this content is unavailable in your country.’ Soon we may all be seeing a lot more of this as well:

This took me three days of puzzling through, so if you liked it, please share this with your friends, leave a comment, subscribe to the newsletter, buy me a Ko-fi, or yell at me on various internet channels.

Footnotes

Or as my dear friend Daragh O’Brien says, ‘5% of a Metaverse’, When you combine it with the already-levied 1.3B EUR fine (as of January 2023), Meta has been fined 10% of a Metaverse.

Specifically, Article 46(1) GDPR. As was found by the CJEU, and the EDPB before it, Meta’s transfers failed to ensure a level of protection for data subjects equivalent to those required under the GDPR, especially in relation to US Government surveillance.

Data Protection Commissioner v Facebook Ireland Limited and Maximillian Schrems (‘Schrems II’), Case 311/18.

These special legal mechanisms are also known as ‘Article 49 derogations’.

The full play-by-play is also available in the DPC decision (notably Section 2, which spans about 25 pages). I’ll note that the decision itself is 222 pages long.

More detailed objections can be found in Section 9.50 of the DPC Decision, which also includes details on the EDPB’s findings and conclusions.

Also known as Article 65 Dispute Resolution. The decision can be found here. The DPC and EDPB have also sparred over another set of cases against Meta/Instagram, which includes a whole bunch of extra spicy drama. See: Robert Bateman, “Irish DPC to Challenge Fellow Regulators in Court Over ‘Problematic’ Direction,” 4 January 2023, GRC World Forums.

That is, until Max challenges that and we get Schrems III and start this whole mess over again.

This is not entirely theoretical. In fact, both the EDPB and numerous members of the EU Parliament have expressed concerns over the current Data Privacy Framework, asserting correctly that it’s effectively meaningless and does nothing to limit the US surveillance state or create “effective equivalence” with the GDPR. Absolutely none of them seem to realize that this is also the case for many EU and so-called adequate countries, but hey, glass houses, stones, etc.

In a LinkedIn reaction post I originally relied on an earlier Statista figure for EU daily users which suggested Facebook had 309 DAUs in the EU. I have revised this to reflect Facebook’s recent DSA Transparency Report. Primary sources, yo. https://transparency.fb.com/sr/dsa-report-feb2023/

‘Processing’ is a broad concept under the GDPR, and Article 4(1) defines it as “any operation or set of operations which is performed on personal data or on sets of personal data, whether or not by automated means, such as collection, recording, organisation, structuring, storage, adaptation or alteration, retrieval, consultation, use, disclosure by transmission, dissemination or otherwise making available, alignment or combination, restriction, erasure or destruction.”

That said, hope springs eternal for some, who have argued that the Executive Branch’s implementation of EO 14086 may be strong enough to address at least _some_ of the CJEU’s concerns. See: Hendrik Mildebrath, “Reaching the EU-US Data Privacy Framework: First reactions to Executive Order 14086,” European Parliamentary Research Service, December 2022.

The US CLOUD Act arose from a legal challenge brought by Microsoft Corp. against a law enforcement demand made against its subsidiary in Ireland. The CLOUD Act provides law enforcement with wide-ranging powers to demand information and data about individuals from US electronic communications service providers (ECSPs) “regardless of whether such [evidence] is located within or outside of the United States.” The determining factor is whether the US ECSP maintains “possession, custody, or control” of the information being requested. Most subsidiaries, affiliates, etc., share data with their affiliated parent or sister organizations, which means that the possession, custody or control question is usually answered in the affirmative. See: Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018, PL 115-141, Division V; 18 U.S.C § 2713.

The 2021 SCCs refer to Standard Contractual Clauses, a set of legal contracts approved by the European Commission in 2021. These are considered the ‘gold standard’ for data processing agreements, and one of the approved mechanisms to allow for lawful transfers outside of the EU. Or at least they were. The relevant section of the DPC’s decision discussing SCCs can be found at Sections 7.170-7.1.73.

Derogations are listed under Article 49 GDPR.

The others being anonymization and pseudonymization. See: Articles 25, 32, & 33 and Recitals 28, 83 and probably a few others I’m missing here.

Here’s a fun one. Go look for ‘lost my recovery key’ on Apple.com or Stackoverflow, and you’ll see some genuinely depressing results.

The Chat Control measures will be discussed in a future blog article, but for the curious, Patrick Breyer offers a brilliant summary of the policy disaster that is currently being proposed by the EU Parliament.

See for example: Brandon Reagen, Wooseok Choi, et al., “Cheetah: Optimizing and Accelerating Homomorphic Encryption for Private Inference,” Facebook Research/IEEE International Symposium on High-Performance Computer Architecture.

The EU is also proposing a number of additional laws that have the potential to cut off the EU across many industries, including the Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act, which implement tight controls on online marketplaces and “Very Large Online Providers” to the AI Act’s potential to cut off AI innovation at the knees.