A Patchwork of Privacy Laws: Unraveling the Consequences of Legal Code Debt

How Quick Fixes and Shortcuts in Privacy Law Create Complex Challenges

Over the last few years, it feels like the rush to be “first” to pass some new ambitious law, or issue some groundbreaking decision or guidance, has spread in the privacy and data protection world. I’m pretty bad at tracking and critically assessing all the developments, but fortunately I follow some brilliant folks who do (you should as well).

What I am better at is being a decent “privacy Cassandra”. That is, I think I’ve developed a reasonable skill in understanding how rushed, ill-thought-out, or politically-motivated laws and regulations can have profoundly negative consequences on the world, and assessing what those consequences are likely to be. All those years of issue spotting in law school apparently have paid off.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about the sense of “privacy urgency” we’re facing. Within the last 3-5 years, in response to abusive business practices, new innovations, shiny tech trends, and the need to grab headlines, politicians, courts, and regulators seem to be pushing hard to protect privacy. The problem of course, isn’t the goal (privacy and data protection are important, fundamental rights), but their approach to solving the challenges I’ve noted.

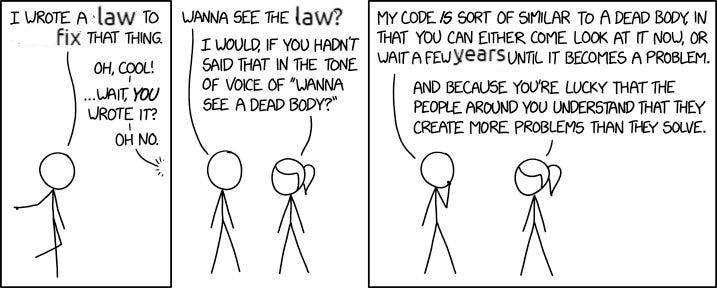

The problem I’d like to explore today is about the legal technical debt that’s being created, especially when laws are passed without thinking of downstream consequences, and how we might be able to solve it (maybe). But first, I need to back up and explain what ‘technical debt’ is.

Good, Fast, Cheap. Pick Two

There’s a concept in project management and software development circles that you’ve no doubt heard before— when it comes to developing a new thing (whether it’s software, a service, launching a new program, passing a law) there are three options: good, fast, or cheap. Pick two.

Good and fast means your code or project will be expensive (either to produce or to run, or both).

Cheap and fast means whatever you turn out will be low quality or buggy.

Good and cheap means the result will be good, but it will take loads of time to produce or be slow to run.

Lots of software is developed based on ‘cheap and fast.' Developers prioritize easy solutions and hacks over well-designed, thought out code. They hack around a problem rather than solve it, or add a comment or line item that they’ll get around to it … eventually.

Over time, these hacks and rushed choices compound into what is known as ‘technical debt’ (or code debt). The ‘debt’ here represents the cost of diminished performance, future interoperability challenges, and increases in the labor and time costs to rework, refactor, and fix all the broken code or correct bad choices created early on.

The concept of technical debt was inspired by monetary debt. As with financial debts, when technical debt isn’t repaid, it accumulates interest, making it harder and usually more costly to correct down the line.1 Like monetary debt, having some technical debt isn’t always a bad thing. A developer trying to push a proof-of-concept or get a minimum-viable-product off the ground isn’t necessarily committing a cardinal sin in programming merely because they’re pushing fast code. Provided that they fix it early, this kind of debt allows for fast failures and iteration.

The problem comes when the technical debt accumulates. A lot of computer security headaches, data quality failures, and poor data governance practices can be traced to the consequences of technical debt not being paid down.

Technical debt also happens outside the programming context, for example when builders cut corners in design, manufacturers build products that have obvious, structural deficiencies that only get discovered after a few people die, and critically, when lawmakers draft new laws in a rush to be first or address a highly-charged political concern.

The latter is what I want to focus on today — what I’ll call “legal code debt”.

Good, Fast & Cheap + Legal Code Debt

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 137 out of 194 countries (71%) have at least one data protection or privacy law on the books. Within the US, every state seems to be gearing up to pass a new law, and within the EU, there are over 100 different laws (enacted, in negotiation, or proposed) that will touch the digital sector and technology, including nearly 20 that directly affect privacy and data protection.2 Here’s a visual representation, based on research done by the Brugel Group in November:

While some nations have taken the approach of crafting a single omnibus law, others have opted for the US-style of lawmaking — lots of sectoral, industry-specific and narrowly-tailored state and federal laws.3

Jurisdictions often take different approaches in terms of classification, scope, or application of their laws. The General Data Protection Regulation, for example, takes a very broad approach to all three. So:

‘Personal data’ means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person;

it relates broadly to any ‘processing activity’, which is any operation or set of operations done to that data; and

it applies to any ‘controller’ or ‘processor’, which is natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body; provided that either the controller or processor is

based in the EU, or

processing personal data about people in the EU.

Contrast that with a highly sectoral law like the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, which only applies to

‘protected health information (PHI)’ that relates to ‘individually identifiable health information’ ‘transmitted by’ or ‘maintained in’ ‘electronic media’ (or transmitted or maintained in ‘any other form or medium’) except when that information is in the context of:

educational records;

employment records held by a covered entity in its role as employer; or

a person who has been deceased for longer than 50 years.

and when that PHI is ‘transmitted or maintained’ by a ‘covered entity’ which includes

a health plan;

health care clearinghouse; or

a health care provider who transmits health information in electronic form in connection with a transaction covered;

or a ‘business associate’ of that covered entity;

related to an ‘individual’ who is the subject of protected health information.

Now, I’m not saying that the GDPR is perfect. Exceptions and peculiarities exist within any law drafted by people, but the exceptions under the GDPR are, well, exceptions, and not holes big enough to drive an entire business model through. Which is to say, a GDPR-like law covers how a fitness app tracker (like Fitbit or an Apple Watch) use my health data; HIPAA does not.4

Applying the ‘good’, ‘cheap’, ‘fast’ model then, it’s worth noting that the GDPR prioritized good, though I’m not entirely sure it did much with fast, or cheap to be honest.

But most sectoral or rushed-through laws prioritize cheap and fast over good. This approach to lawmaking is taken for a number of reasons. Firstly, politicians want to be seen as ‘doing something’, but lack the expertise to do it right, so they do it fast (fast). Second, it’s usually easier politically to draft a limited-scope law wide gaps that won’t piss anyone (important) off (cheap). Third, lobbying. So much lobbying and influence peddling dictates what’s in a law that it hurts (also cheap).

But fast and cheap legal code is developed because governments and supranational organizations need consensus to pass laws, and an inoffensive niche law that affects a small subset of actors who lack lobbying power is almost always easier to pass than a broad, omnibus law that covers everybody and has teeth. Sadly, I predict this will only get worse over the next decade. The recent passage of the AI Act in the EU5, and other headline-grabbing laws being proposed and passed in Europe, the US, the Middle East, and Africa aren’t helping.

Dealing with the Debt (and Interests)

The rush to pass fast and cheap laws, like fast and cheap software, is an understandably human one. I get the sense of urgency that regulators and lawmakers face to rein in Big Tech and counter creepy new invasive practices like real-time facial recognition and AI.

But I don’t think enough people, and certainly, not enough regulators or politicians, are thinking about the bigger picture and downstream issues that come from this approach. Now instead of siloed laws riddled with legal code debt within a jurisdiction, we’ll get siloed, legal code debt between multiple jurisdictions. And this debt compounds with interest as each new law passes.

For example, how do we reconcile differences and inconsistencies between the laws we already have? If you’re a business operating around the world, do you adopt the law with the broadest application to cover all the bases, the most permissive law because you figure you’ll never get caught, or the one based on where your headquarters are located? How do you keep up with the individual edicts of each law and their implementing regulations? What happens when there’s an conflict between two or more laws (for example, when one law demands ‘explicit’ user consent before processing, while another allows for other lawful reasons to process information).

I foresee that this will lead to a few outcomes, most of which are not particularly great for protecting people or their fundamental rights.

Patchwork Compliance. The most likely outcome, of course, is what we have today — companies will attempt to comply and expend a lot in doing so. This represents a fantastic business opportunity for consultants and lawyers like me, but absolutely disastrous for everyone else — including individuals whose rights these laws are intended to protect. We’ll also get a rehash of what we see today — weak compliance, consent-spamming, confusion, and/or region/country blocks as some companies rationalize that it’s much easier to foreclose on a market than to comply with myriad laws. We might even see this within the same country (looking at you, Washington, Texas, Florida, Illinois).

Gaming the system. The biggest firms with the largest compliance and lobbying budgets will of course, have an easier time finding loopholes and exploits in the law, carefully ignoring the aspects that negatively impact their bottom lines too much, and engineering clever legal workarounds and justifications to navigate divergences when they can’t. They’ll budget in compliance and regulatory costs as part of doing business. The biggest companies will also doubtless get bigger as patchwork compliance costs eat into smaller-margin firms profitability. Maybe a few of the worst practices might change, but that change will take years, and will be inconsistent. It already is.

We've seen this play out for decades now in copyright law. Mike Masnick on Techdirt discussed in a recent piece about how the legal code debt rife in most copyright laws has translated to a wide array of negative outcomes. Instead of protecting artists or small content creators, copyright has been weaponized by publishers, major content players, and other antagonists to stifle competition, extract exorbitant rents, curb speech, erase facts, and erode culture. Companies like Spotify play games with licensing and payments, because they have the resources to exploit the law and know that they can weather the consequences if some small artist tries to sue. The only people who actually benefit are the organizations that have enough power, money, and clout to arbitrage the law.

Everyone gives up. There is a point where reconciling the laws might become completely impossible or unworkable. Everyone is directly/intentionally, or indirectly/unknowingly guilty of violating the law in some way. Either because the law contradicts other, perhaps more relevant laws, is too vague to interpret properly, is unknown or unknowable by the people it covers, or isn’t enforced enough to matter. Sometimes, someone somewhere might be fined or thrown in jail, but often as an excuse to target a disfavored person or group. It’s like when cops stop and arrest people for jaywalking or a having a busted tail light. The stop is almost always a pretext, an excuse to go after someone for something else. Many state data breach laws fall into this category — nobody knows how, or can reasonably comply with the volume of data breach notification laws out there, most of which differ in subtle, tricksy ways. Occasionally someone might get dinged, but the instances are rare, and usually an excuse to go after other underlying issues.6

Is it Time for a Privacy Union?

I recognize that my analysis looks pretty grim (I did warn you, I’m a Privacy Cassandra), but I do think there might be an approach of sorts that could work to correct at least some of the legal code debt. We might be able to take a page, for example, from the Universal Postal Union.7 The UPU, established in 1874, is among the oldest existing intergovernmental organizations.8 The goal of the UPU is an ambitious one — to fix a pressing legal (and process) debt of the day — exchange of mail between countries. As they explain on their website:

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the exchange of mail between countries was largely governed by bilateral postal agreements. But by the 19th century, the web of bilateral agreements had become so complex that it began to impede the rapidly developing trade and commercial sectors. Order and simplification were needed in the international postal services. …

On 9 October [1874] … the Treaty of Bern, establishing the General Postal Union, was signed. Membership in the Union grew so quickly during the following three years that its name was changed to the Universal Postal Union in 1878.

The 1874 Treaty of Bern succeeded in unifying a confusing international maze of postal services and regulations into a single postal territory for the reciprocal exchange of letters. The barriers and frontiers that had impeded the free flow and growth of international mail had finally been pulled down.

There’s lots more to this story, and the stories of other international standards bodies and initiatives designed to reconcile legal divergence, such as the Council of Europe and the Convention 108+ protocol. This is an idea I plan to explore in future pieces as a possible way to work around the fractal complexity, and legal code debt challenges we face today and will see more of in the future.

While we navigate this mess, let’s not forget the ultimate goal: to create a framework that offers more than lip-service and exploitable compliance headaches — one that meaningfully respects our fundamental rights, ensuring a balanced digital world for all.

The concept of technical or code debt came from Ward Cunningham, a computer scientist, and co-author of the Manifesto for Agile Software Development.

Data based on my own research reviewing and categorizing the EU’s ‘Legislative Train Schedule - A Europe Fit for the Digital Age,’ and the Bruegel report (Authors: Kai Zenner J. Scott Marcus Kamil Sekut), which analyzed EU legislative measures in depth.

I suspect that the US is batting well above average on the total number of state (currently 12, according to the IAPP) and Federal laws floating around.

Now, you might argue that HIPAA’s an easy one to pick on — the law was drafted in 1996, and has had numerous iterations, regulations, and even a bit of legal code debt cleanup in the form of the Administrative Simplification Rules. Still, I don’t think HIPAA is unique, and I worry that other countries are moving towards the HIPAA model, rather than away from it. NB: A massive shout-out to the folks at the HIPAA Journal who have tirelessly done the hard work of explaining HIPAA in a sensible way. I am not a HIPAA expert, and the resources they offered were helpful in crafting this section and example. Credit where credit’s due.

Which despite a two-year drafting window appears to have been rushed through at the very end to meet political deadlines in the European Parliament.

The Texas and Florida social media disasters will also meet this fate, assuming the Supreme Court lets them stand.

Don’t laugh. This is actually a thing, and something I discovered strangely enough, while trying to argue with An Post (Irish postal system) in the hopes of finding out what happened to a Christmas package that I have been waiting a month to receive.

As my dear husband informed me, the UPU is only the fourth oldest intergovernmental organization. It was beaten out by the Central Commission for the Navigation on the Rhine (1815) and the Danube Commission (1856), followed by the International Telegraph Union (ITU) in 1865. The International Bureau of Weights and Measures opened a year after the UPU, in 1875 to make the top five.

"Technical debt also happens outside the programming context, for example when builders cut corners in design". Like when you build a house with a roof line that doesn't send water away from the building!

This is great, my favourite piece that you’ve written so far! One question: do you think that the good, fast, cheap model applies to the ‘enforcement’ of laws as well as the ‘making’ of laws? Would you say that the enforcement of the GDPR has been mainly cheap and fast for at least some data protection authorities, or do you have a different view?