I Built an AI-Powered Futures Forecasting Pipeline With Claude Code

Here's how I did it and what I learned. Plus, humor, cats, and link to the source code.

So, I have another confession to make: I am a serious info-junkie. News, papers, books, law reviews, statutes, Substack articles, I don’t care. Hell, I even catch myself reading the Google chum bucket on my phone sometimes. Also, my info-junkie habit is wide, but not necessarily deep. Fundamentally, I want to know a little about everything.

But, the challenge with being an information junkie is that there’s always more content than time. Well, that, and the content is frequently depressing and sometimes poorly written, but these are different problems entirely. And while I’m unlikely to fix the other issues in my life or society, I realized that Claude and Python could probably help me manage my addiction to information a bit better.

The problem: Monitoring 122 RSS feeds for particularly interesting signals is impossible to do manually.

The vision: Build an automated keyword filter that parses RSS feeds, sends the result to AI for summarization, and pipes everything into my second brain (Obsidian). I have written about it, how I use it, and tools I’ve already developed here, here, and more recently here.

Well, I have good news—I think I finally have a tool that meets my needs. It’s been months in development, but now it’s good enough that I’ve decided to release it on GitHub.

Here’s the journey I’ve taken over the last 8 months, using Claude Code.

Phase 0: Whatever you Do, Write a Design Doc First

As I’ve mentioned before, I can’t code for shit, but I can give very precise instructions to an LLM like Claude Code. Fortunately, Claude Code is very good at coding, and I am reasonably ok at noticing when Claude has gone off the rails, is having notions, or doing something I don’t want, so if you squint hard enough, this is what the C-Suite might label as “pair programming”. Plus, Claude Code also runs locally on the command line in Bastard Linux (aka, Windows Subsystem for Linux), which means I don’t have to constantly deal with the problem of Windows line-break fuckery. IYKYK.

But, before you get ideas and want to code things, let me share some wisdom:

For the love of god, write a design doc first and keep it updated.

Was that explicit enough?

Even if you think design docs are stupid and a big waste of time and you aren’t writing anything for promo, you should do it anyway, or at a minimum, have Claude Code bang one out. Tell it what you want, step-by-step, and have it outline a basic design framework to follow that you understand and agree with. This is important for two reasons:

Claude has finite memory and will forget things when it has to compact, and it completely forgets everything when you close the window. A design doc grounds Claude by providing it a starting point to work from every time, and keeps it from burning tokens reading your code from scratch.

If you’re anything like me, you also have a finite memory. Having a design doc reminds you of what you want, and where you are in the process.

Also, build in testing, and be better about Github commits/version control than I am. I hate Github.

Finally, I recommend using Python as your language of choice because Python has more libraries for handling data and interfacing with Claude/ChatGPT/etc. than most other languages, and yet it’s still vaguely accessible to normies who don’t program for a living. But hey, if you want to bash this out in Go or Rust or whatever, via con dios.

Phase 1: Build a Basic RSS Reader with Custom Keyword Filtering

Phase 1 was all about starting from the basics, and the first step was building a simple RSS reader that could parse keywords. RSS readers are amazing at website aggregation, but managing the output is akin to getting blasted in the face with a firehose, especially if you’ve got hundreds of feeds to parse like me because you have problems with FOMO. While you can tailor some individual RSS feeds to search for a keyword or two, this often doesn’t scale, and it tends to be futzy, because not all RSS feeds are properly formatted, and some don’t even follow the RSS standard properly.

To give a rough idea of what 122 feeds might look like, assume that, on average, each feed URL has 5 articles a day each (some feeds rarely update, but others have like 20 feeds, and I’m using simple math).

That’s 610 articles to skim through a day.

Assume that it takes approximately 20 seconds to skim each article, so that’s 12200 seconds or approximately 3.5 hours devoted to just looking at the headers and making a snap judgment to click or not.

Let’s say of the 610 articles, 25 of them catch your eye. Assuming it takes you 4 minutes to read most articles, that’s 6000 seconds, or a bit over 1.5 hours to read everything. So in total, 5 hours to process all your feeds. In the immortal words of Sweet Brown: ‘Ain’t Nobody Got Time For That.”

What I needed from my new and improved reader was something that could:

Take individual feeds and grab the URLs/content;

Open each link and do a basic grep (aka, fancy CTRL-F for the non-Linux nerds) over a list of provided keywords; and

Send back only results that included the relevant keywords I care about.

With Claude’s help I got a MVP up and running over the course of a weekend. It was adorably small (~200 lines of code), and I could specify RSS feeds and keywords in customized files. It ran from the command line, and allowed me to specify a few parameters (like the source files for keywords and RSS feeds, and the number of days to search). Results were initially output and stored in an /output/ folder as a .txt file, but I pivoted quickly to HTML because .txt files are ... unpleasant. None of it was pretty, and there was no UI to speak of, but it worked!

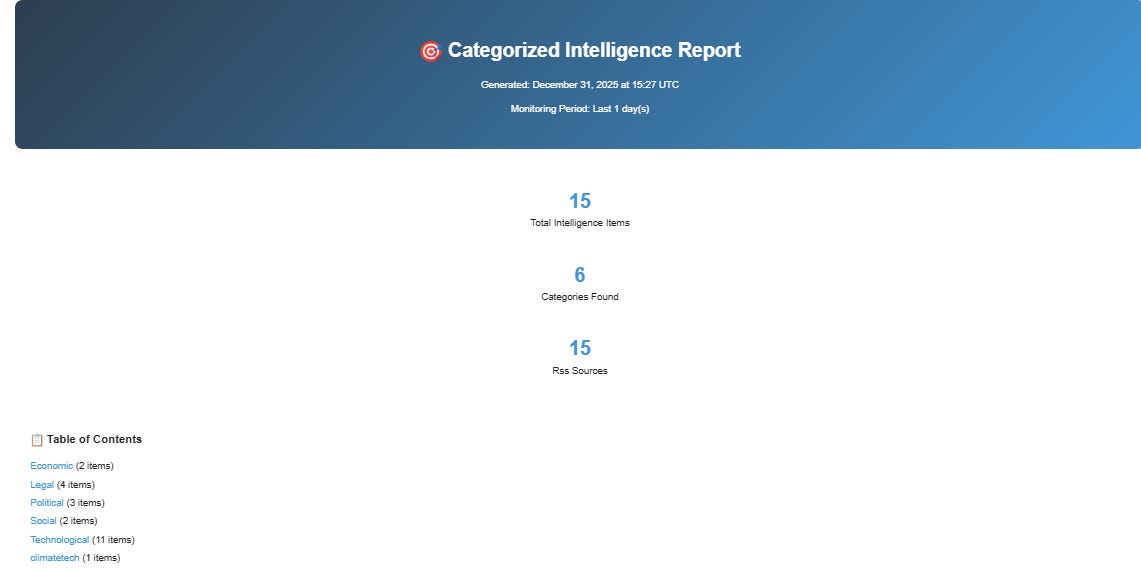

Over the next few months, I worked on various improvements with Claude. For example, I improved the UI by adding in a ‘snippets’ function that would include a few lines of text around the keywords, and making the HTML output look pretty by grouping and organizing results into high-level keyword categories, with some statistics (# of items and keywords, total RSS sources). I did a better job manually curating and keywords into different categories (e.g., Social) & sub-categories (e.g., Advocacy) to make classification easier/more sensible output-wise, and it also makes it much easier when adding new keywords.

I also built in some de-duplication functionality (using Pickle), which scans a dictionary of processed URLs and ignores articles that have already been downloaded / reviewed for keyword matching.

But mostly, I spent time squashing bugs. So many bugs. It turns out that real-world data is messy. For example:

Welcome to Timezone Hell

I still get this error (or variants):

UnknownTimezoneWarning: tzname EST identified but not understood

It turns out that some RSS feeds still use EST/PST/GMT, etc. instead of proper timezone formats like UTC. Claude’s solution: default to UTC and be aware some timestamps are approximate, and include the article anyway. This helps in most cases. Also, include error handling, don’t just crash the processing at runtime, lol.

UTF-8 Isn’t Universal

Are you one of those people who think standards are actually followed?! What are you, new?

Despite UTF-8 being “standard,” some feeds send broken encodings, special characters break filenames, and HTML entities get mangled. BeautifulSoup and defensive string sanitization saved me.

Other Weird Fuckery I Didn’t Realize Was a Thing Before This Project

OPML files with unescaped ampersands break the process, because, it’s 2026 and everything is terrible.

The fix: Replace unescaped ampersands before parsing

fixed_content = re.sub(r'&(?!amp;|lt;|gt;|apos;|quot;)', '&', content)

root = ET.fromstring(fixed_content)Three & Four Letter Acronyms create noise pollution.

The fix: Spell out short acronyms to avoid triggering irrelevant words. For example, don’t use AI (which will grab everything (AI, airplane, taint, bait), use artificial intelligence. Sync (will grab synchronize, synchron, synchronicity, etc).1

Feeds that claim they’re RSS but return JSON, txt, HTML or something else.

The fix: Data cleansing is important -- hence Beautiful Soup.

Lessons I learned from Phase 1

Have a design doc.

Build small and iterate often.

Be liberal with comments. I freely admit I didn’t write any of this code (bar a few simple tweaks). Comments are like breadcrumbs, and very helpful when you’re looking at code months or years down the line.

It doesn’t have to be pretty at first, it just needs to work. Then you can make it pretty.

Do regular code commits to Github for version control.

Be prepared for things you did not expect to break breaking.

Have something soft or comforting nearby to pet, so that when you find a problem that inspires rage, you can remain calm and collected.

Build in graceful fallbacks, and testing.

Don’t assume standards are actually followed. Everybody is winging it.

Phase 2: Please, Free Me From Toil

I Am a Slow Reader and Prone to Distraction

Eventually, with Husbot’s help, I set my script to run daily as a cronjob in Linux and send the output to Gmail, which was handy. By this point, the name of the program had morphed from ‘RSSKeywordParse.py’ to ‘makeitmakesense.py’, to parallel my continued descent into madness. I really am not cut out to be a programmer. The email output looked like this:

Still, the program was running, and I had a pretty email digest to review. But so much of my process remained very, very manual:

Run makeitmakesense.py automatically each morning (automated)

Read the email snippets and click on relevant links—sometimes 5, sometimes 50. This usually took around 30 minutes to an hour, depending on volume. (manual)

Use Leo AI in Brave to summarize each article with a custom prompt, and briefly skim the article just to see if Leo was hallucinating. This usually took anywhere from 3-4 minutes per article. (semi-automated)

Copy the summary & paste it into the Obsidian Web Clipper, which saves the file as a markdown directly in Obsidian. Approx 20 seconds per article. (manual)

Run various community plugins on each article. This took a few seconds. (manual, but with keyboard commands)

Review the article and add tags, relevant information, or inferences not identified. This usually still takes time. (manual, but fun)

Repeat 20- ∞ times.

This translated into something like the following:

6am: Cron job runs → HTML email arrives.

7am: Me, with coffee in hand, clicking through 30 tabs.

8am: Review articles, and start copypasting summaries into Obsidian Web Clipper.

8:15am: Get distracted/pet a cat/have to do other work/reload Brave because it crashed from 30 tabs being loaded at once.

9:30am-11:00am: Finally done with “research” (really just data entry). Now on to fun stuff.

So, while things worked, and it was better than the alternative, a lot of manual toil remained. And if the news was particularly active, or my computer didn’t run for a few days? It could be hours.

The bottleneck wasn’t finding articles—the keyword filter worked great, and de-duplication kept the numbers reasonable on average. The bottleneck was the repetitive summarization and data entry work. I was essentially a human API between Gmail, Leo AI, and Obsidian.

Computers Read Faster Than I Do, Can Serialize, and Don’t Need to Pet Cats or Get Paid

Over the next few months, I tried various ways to automate some or all of these steps. It wasn’t until New Year’s Eve, midway into enjoying a vintage Bruery Black Tuesday whilst confronted with a backlog of 300 articles to process, that I realized there was a better way. I do my best “coding” whilst drunk.

What I needed was for Claude to do the initial triage, review, and summary for me, essentially eliminating steps 2-4, and then dump those results into Obsidian. Then I could skim summaries (not snippets), and read and process articles that I actually cared about, and build cool mindmaps that would help with actual future forecasting. Y’know, the fun stuff!

Things again started slowly. First, Claude and I built a separate tool (helpfully named article_processor.py) that would:

take a keyword-selected article from the /output directory;

send that content (in markdown), along with a custom prompt to Claude via the API. This was the prompt I used for Leo, and after much trialing and erroring, it worked really well;

Claude would process and summarize the article, auto-tag keywords, and create formatted, Obsidian-friendly frontmatter;

files would be returned in a /processed folder (and later, directly into my Obsidian vault).

To overcome some of the technical problems discussed in Phase 1 (notably article-fetching from websites that didn’t play nicely), Claude added some integrations with two tools--trafilatura and Jina Reader (as a fallback) to handle article content fetching.

So, now there’s one command that executes across five steps. And the Claude processing step is behind a flag, so you can easily just use the RSS Keyword functionality without Claude.

My total process now is down to around 90 minutes, because I only need to review things in Obsidian once.

Key Components:

makeitmakesense.py (now feedforward.py): handles RSS aggregation, keyword filtering, HTML reporting.

article_processor.py: handles content extraction, Claude summarization, note generation.

.env configuration: allows for customizable API keys, file paths, rate limit settings, input files, email forwarding, etc.

structured keywords (keywords.txt): Category-based taxonomy for better filtering -- this makes it easier for later classification/tagging.

Bit Let’s Not Forget the Bugs…

Rate-limiting: Claude API has a limit of 30,000 tokens per minute.

The fix: With 300 articles, we hit this constantly. But API rate limits are a constraint to design around, not a problem to fight. Treat it like a Goldilocks problem—find the happy middle. Pick a small number of articles to process in a batch. Start with something like 5, but don’t be surprised if you need to lower that to something like 3. Add in wait periods and retries:

for attempt in range(max_retries): try: # Ask Claude to summarize message = self.client.messages.create(…) return summary except RateLimitError: # Wait longer each time: 2s, 4s, 8s, 16s, 32s wait_time = (2 ** attempt) * 2 print(f"Rate limit hit, waiting {wait_time}s…") time.sleep(wait_time)

Build in different approaches for article fetch fails & paywalls: RSS feeds return 403s even for standard user agents, articles that return “Subscribe now!” or paywalls.

The fix: Have multiple pathways built in to grab articles. Find workarounds or at least fallback gracefully. Don’t let one bad article spoil the fun. But do keep track of failures.

Method 1: Try the fast, simple approach

content = trafilatura.extract(url)

if content and len(content) > 200:

return content # Success!

Method 2: If that failed, use Jina AI Reader (handles tricky sites)

jina_url = f"https://r.jina.ai/{url}"

content = await session.get(jina_url)

if content:

return content # Got it!

Method 3: Give up gracefully

return None # We tried our best

Actually review what your coding agent/pair programmer is doing: Claude will confidently lead you off a figurative cliff if you let it. It is not real, and will happily make shit up. Granted, it’s better now, but even a well-grounded system with guardrails like Claude can get stuck in tangents and loops. For example, I caught Claude:

Creating files in the wrong directory (fixed by checking before accepting edits)

Misunderstanding which files to edit (parent vs. subdirectory confusion, which admittedly was partly my fault)

Adding complexity when simplicity was better (it initially proposed a very convoluted MCP server, when a simple API call was better)

Going off on tangents when I asked vague questions

The fix: Read code changes. Be very stingy with giving it unfettered approval to do commands on your machine. Ask clarifying questions. Claude is a copilot, not an autopilot. At least for now you’re still much smarter than the LLM, and you need to treat it like a gifted, but overconfident, cocky intern, not an oracle.

Lessons Learned in Phase 2

Read the code. At least have a vague idea of what it’s doing. Ask Claude for help when you need it. Comments help!

Give your tools detailed instructions to avoid sadness. Explicit > implicit when working with AI. Over-communicate the steps. Describe exactly what you want, step-by-step, even if it seems painfully obvious. Pretend you’re instructing an interdimensional alien on how to make a peanut butter & jelly sandwich. This often included telling Claude to regularly look at the code (or design doc) again from time to time and explain why it made the choices it did. 2

.env is Your Friend. Fight the urge to hard-code things into your source. Learn—or have Claude explain—how .env (environmental variables) work and stick all your sensitive stuff in there—API keys, passwords, local storage locations, preferences.

Even if you don’t think you want to make your code public, it’s still a good idea. And who knows, you might be like me and change your mind and decide to make it public.

Roadmap & Future Improvements

I will probably continue to iterate on this program. Not only is it fun, but it’s hella effective for my specific needs. Here are a few of my planned features, but if you think of something that would be cool, let me know (or better still, fork the repo and share the changes).

🔮 Future enhancements

Quality scoring (skip low-quality content)

Multi-language support & translation (there’s loads of non-English content out there)

Custom summarization prompts per topic/category

Integration with my Obsidian Mind Meld plugin (auto-run after processing)

Web interface for review

Claude-suggested keywords based on missed articles/context/themes

Better error-logging

Multi-LLM support3

Citation extraction—Automatically pull out referenced papers, people, organizations

Trend detection & forecasting—Identify emerging topics & trends across time

Semantic & Network analysis functionality

Collaborative filtering—If multiple people use this, share anonymized trend data

Technical debt I still need to address

Better timezone handling: Parse all timezone formats properly. The frequency of this error has decreased, but it still exists.

Test coverage: Add automated tests for core functions. I am genuinely bad at writing tests, a point that Husbot regularly reminds me of. He is right of course.

Modular architecture: Break into smaller, reusable components.

Configuration UI: Web interface for managing feeds/keywords instead of text files. Right now, everything is based on the command line. This is fine for me, but may not work for others less familiar with the arcana of Linux.

Wrapping Things Up

Well, if you made it this far, take a drink. Also, here are my other coding companions:

In short, this project has been fun and educational. What started as a simple RSS reader has gradually morphed into a full-grown automated intelligence pipeline. And it’s something I actually use (almost daily). The key wasn’t having the perfect design upfront—it was:

Building incrementally

Expecting (and handling) failure gracefully

Working collaboratively with AI tools while staying in control

Iterating based on real usage

The system now saves me hours per day of manual research work and lets me focus on analysis (which is way more fun) instead of aggregation and data gathering (which sucks).

Here’s the Github repo, if you’re curious, have thoughts, or would like to play with it on your own. Please let me know if you have ANY suggestions or notice any clownish stuff. Check out SETUP.md in the repo—it takes about 30 minutes to get running with your own feeds and keywords, unless you’ve got an OPML file ready.

Claude informs me that there is some sort of context-based keyword matching that uses whole words instead, but I think this is a fantasy and I haven’t had a chance to fix it yet. It’s on lines 308-336 if you’re curious.

I recognize that this is neither intuitive, or easy. The only reason I think that I have a leg up on getting LLMs to obey my commands is because I’m a secret dom who has been married to the precursor to ChatGPT since 2013.

It continues to amuse me that Claude always defaults to suggesting competitor models for doing API calls. The number of times it defaults to suggesting ChatGPT as the inference engine of choice is unreal. I understand that this is because of training data bias, but FFS Anthropic, be proud of your own ingenuity.

Congratulations on your project! 🎉 I’ve build tools around RSS feeds before (they’re such a PITA!), so I know how much work this was, even with help from Claude!

Thank you for sharing your step-by-step process. 🙏 Very helpful!

Fascinating! Will you be using this process in your futures practice or was it intended more as a knowledge management challenge?

I keep reading about the brilliance about Claude Code and am slowly but surely getting FOMO.