Privacy Disasters - LinkedIn Spies With its (Not-So) Little AI

This one's a bit different from a normal PD because I actually have something positive to say for once. No, not about LinkedIn, but about the Digital Markets Act.

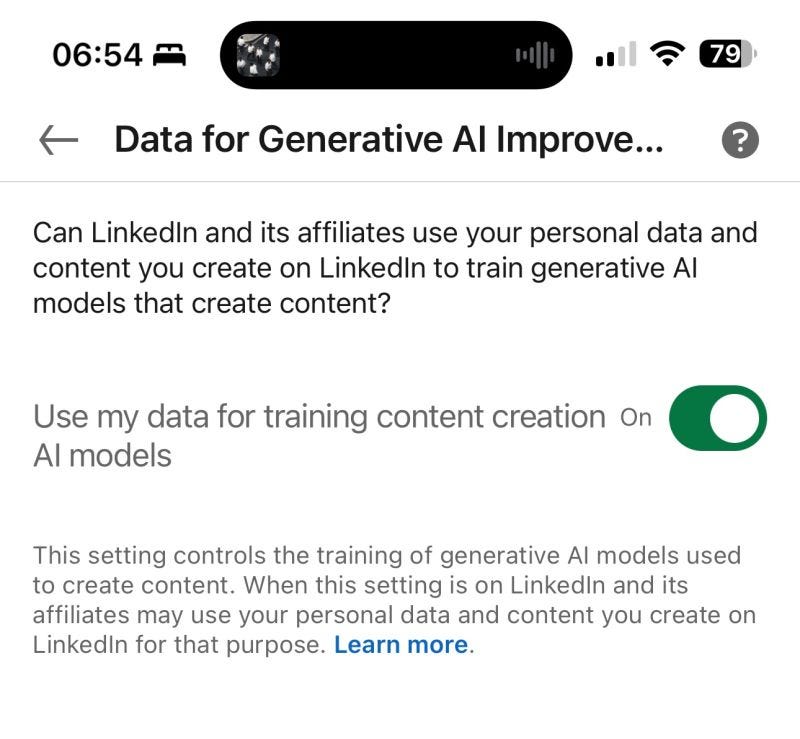

At this point, if you’re vaguely adjacent to the privacy / data protection / cybersecurity or hell, even a active LinkedIn user, you’ve seen the news that LinkedIn auto-enrolled nearly everyone into its generative AI training. I first heard about it from Kevin Beaumont.

PSA: LinkedIn are training AI models and selling data for training AI models from your posts, and the setting is enabled by default. I suggest you disable it unless Microsoft pay you.

This basically erupted into an all-out war on LinkedIn. If you do a search for ‘data for generative AI’ or ‘LinkedIn AI default’ you’ll see loads of results — various degrees of explanation, swearing & outrage, and helpful guidance on how to disable the ‘feature’. This thing epitomized privacy disaster. Or y’know…

FWIW, you can go here to disable this shameless, legally-dubious content grab. Notice I said ‘nearly everyone’. If you’re in the EU/EEA or UK and click that link, you’ll be greeted with the following message:

Initially, I was surprised that no opt-out existed in Ireland, and based on the comments in Kevin’s feed, other parts of the EU. But then I remembered something: The EU Digital Markets Act.

There’s also, of course, our old reliable friend, the GDPR to consider, but for today’s post, I want to focus on the DMA because I don’t think it’s getting enough love.

The DMA: Moving Away from Individual Consent Towards Societal Control

The Digital Markets Act (Regulation (EU) 2022/1925) is laser-focused on some of the worst privacy and data protection offenders: the gigantic digital platforms that use network effects and their market influence to enshittify the internet. The goal of the DMA is to ensure a higher degree of competition in European digital markets by preventing a subset of bigtech companies (referred to as ‘gatekeepers’) from abusing their market power and harming consumers. There’s some laudable aims to also encourage new players and innovations in the market, but we’ll see how successful that is amidst all the other sometimes conflicting, regulations, directives, and regulatory oversight mechanisms also present in the EU.1

Much of the DMA is premised on traditional competition law, not data protection, so you might be thinking: Surely Carey has been day-drinking again; she’s not a competition lawyer or policy wonk.

I promise you though, there’s loads in the DMA that make it a good thing for data subjects and data protection nerds like me — and I’m going to use the LinkedIn privacy disaster to explain why.

First off, we need to get a tad into the weeds of the DMA, and in particular things like scope and the responsibilities of gatekeepers.

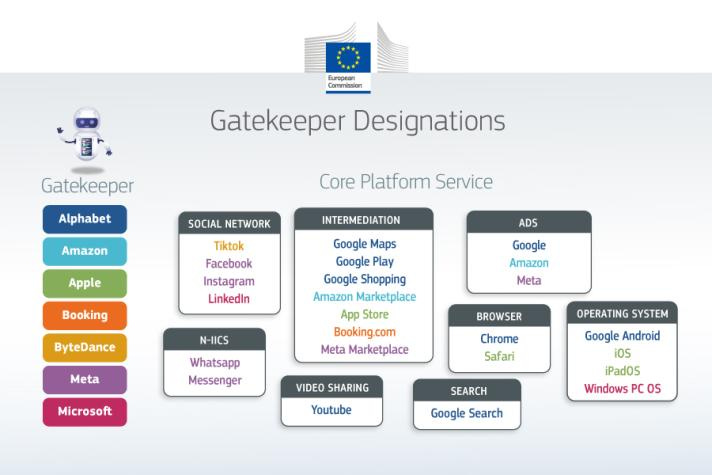

Unlike the GDPR, or most other EU laws, the DMA is extremely narrow. It currently applies to only seven gatekeeper companies, and within those companies, only to designated ‘core platform services’ they offer:2

Here’s the list of companies and the covered services:

Alphabet (Google): Google Ads-based products, Search, Maps, Play, Shopping, Chrome, Android, & Youtube

Amazon: the Amazon Platform & Amazon Marketplace

Apple: Safari, App Store, iOS, iPadOS

Booking.com

ByteDance: TikTok3

Meta: Meta/Facebook Advertising, Meta Marketplace, WhatsApp, Messenger, Facebook.com & Instagram

Microsoft: Windows, LinkedIn

A ‘core platform service’ refers to any of the following services/products. Most of these are pretty obvious, but I have added some explainers for a few of the more EU-y terms of art:

(a) online intermediation services — essentially, any online marketplace or service that allows businesses to offer goods or services directly to consumers (Google Play, Amazon Marketplace, etc.);

(b) online search engines;

(c) online social networking services;

(d) video-sharing platform services;

(e) number-independent interpersonal communications services — non-telephone-based text messaging, like WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, Signal;

(f) operating systems;

(g) web browsers;

(h) virtual assistants;

(i) cloud computing services;

(j) online advertising services, including any advertising networks, advertising exchanges and any other advertising intermediation services, provided by an undertaking that provides any of the core platform services listed above.

But it’s not enough to offer a cloud computing service, web browser, or social networking service — to be designated as a gatekeeper by the Commission, a company (or undertaking) must also:

have ‘a significant impact’ on the EU market;

provide a core platform service which ‘is an important gateway for business users to reach end users;’ and

'enjoy an entrenched and durable position’ (either currently, or in the foreseeable future).4

The entire gatekeeper designation outlined in Article 3 DMA is exceedingly well-tailored to hit the biggest of tech companies — and virtually no one else. Truthfully, the EU would have been within rights to just call this the ‘Go Fuck Yourself, GAFAAM+ Act’.

And while the EU Commission has some discretion in naming companies and designating core platforms, I’d wager solid money that any company added to the list won’t be a spunky upstart tech company, or a mom & pop — it’s gonna be a big bad that earned the designation.

Microsoft, which owns LinkedIn, is such a gatekeeper, and LinkedIn is considered a core platform. Hence why things are a bit different in the EU.

The DMA imposes a number of obligations on gatekeepers in relation to their core platform offerings. While the whole list of obligations is spelled out in Chapter III (Articles 5-15), the stuff that’s relevant to this case falls under Article 5.2. I’ve bolded the sections that are relevant:

Article 5, Obligations for gatekeepers

1. The gatekeeper shall comply with all obligations set out in this Article with respect to each of its core platform services listed in the designation decision pursuant to Article 3(9).

2. The gatekeeper shall not do any of the following:

(a) process, for the purpose of providing online advertising services, personal data of end users using services of third parties that make use of core platform services of the gatekeeper;

(b) combine personal data from the relevant core platform service with personal data from any further core platform services or from any other services provided by the gatekeeper or with personal data from third-party services;

(c) cross-use personal data from the relevant core platform service in other services provided separately by the gatekeeper, including other core platform services, and vice versa; and

(d) sign in end users to other services of the gatekeeper in order to combine personal data, unless the end user has been presented with the specific choice and has given consent within the meaning of Article 4, point (11), and Article 7 of Regulation (EU) 2016/679.

Where the consent given for the purposes of the first subparagraph has been refused or withdrawn by the end user, the gatekeeper shall not repeat its request for consent for the same purpose more than once within a period of one year.

This paragraph is without prejudice to the possibility for the gatekeeper to rely on Article 6(1), points (c), (d) and (e) of Regulation (EU) 2016/679, where applicable.

… [loads more follows, but it’s related to reporting, interoperability, payments & advertising]

Recital 36 of the DMA also has some thoughts:

…To ensure that gatekeepers do not unfairly undermine the contestability of core platform services, gatekeepers should enable end users to freely choose to opt-in to such data processing and sign-in practices by offering a less personalised but equivalent alternative, and without making the use of the core platform service or certain functionalities thereof conditional upon the end user’s consent.

And like the GDPR’s version of consent, it must be a meaningful choice (‘freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous’), and as easy to opt-out as to opt-in. Oh, and you need to provide transparency first (which did not happen).

The DMA’s Capacity to Change Behaviors

On Friday, after days of hot takes both on and off the platform, LinkedIn went into damage control mode. Denis Kellerher, the Head of Privacy for EMEA, had the thankless task of begging forgiveness, as you do when the product teams and execs either fail to consult with, or outright disregard/ignore the advice proffered by any competent DPO — which is to say, don’t do it like this, you eejits.

Kellerher confirmed that user personal data and content of individuals located in the EU/EEA, UK & Switzerland were not included in the LLM data-grab, and would not be for the foreseeable future. He did not mention the DMA, but he did (wisely) disable his comments. He also promised that the LI terms of use / privacy notice would be updated accordingly.

As I wrote in response, this whole thing was an unforced privacy disaster that LinkedIn could have avoided if:

the product teams and VPs listened to their data protection folks;

they treated their user base like actual human beings, instead of mindless content-generation monkeys (fairness);

they provided users with details on the AI rollout and how user content & personal data would be processed, prior to enabling AI training rather than after (transparency);

they set the toggle for all users (not just those where the law demanded it) to OFF by default (privacy by design and default);

they explained precisely why the EU/EEA/Switzerland and the UK would be treated differently (for the EU/EEA, it's probably a combo of the Digital Markets Act & the GDPR; for the UK, it's probably the UK GDPR and the ICO yelling at them).

That last one isn't a principle, so much as a pragmatic suggestion. Legal obligations often have major impacts on business choices. Sometimes it's good to provide context for why different locations are treated differently to avoid confusion and wild speculation that can further damage an organization's brand. Part of the outrage was expected by virtue of rake-stepping on the first three points; but part of it was confusion as to why the EU/EEA et al., is being treated differently.

This episode, in my opinion, also provides a solid case study demonstrating how the Societal Structure Model (as articulated by Professors Hartzog & Solove) can be applied to force better organizational behavior. I discussed this (and the deficiencies in the current notice & choice approach we have today), in my Gikii talk a few weeks ago:

The DMA sets limits on organizational power (in this case, a gatekeeper’s ability to co-opt and combine personal data across ‘core platform services’) in a way that is likely to force meaningful change. It’s a better tool than the GDPR in this regard, because it’s both targeted, and carries stiff penalties for non-compliance — between 10-20% of worldwide turnover for non-compliance, and repeat non-compliance, respectively. There’s a private right of action as well.

The enforcement also appears to be more centralized: unlike the GDPR the major enforcement body is the European Commission. That means one regulatory body instead of dozens. It means less paperwork and bureaucracy, less infighting and conflicting standards, and less delay. This is evidenced by the fact that the EC has issued at least 14 decisions against gatekeepers (including a handful of decisions around Article 5), all within the last year and change.

More importantly, it’s seamless to the user and to the vast majority of organizations that don’t have the network effects and monopoly power to pull these kinds of tricks.

There are no cookie walls, no unnecessary friction, no consent-or-pay bullshit. The DMA rightly puts obligations back on the entities who control these systems, rather than adding a cognitive tax on individuals and a compliance burden for everyone.

I suspect that my US friends (and those in other jurisdictions with existing rights protections) might start asking their legislators ‘Why can’t we have this?’ instead of just carping about unnecessary compliance burdens and parroting the Chamber of Commerce/libertarian anthem of ‘individual choice!1!!!1’

Or who knows: Maybe the likes of LinkedIn will decide it’s easier to comply with the DMA than not, and apply this across the board to all users. Maybe they’ll decide to do the right thing for once, instead of stepping on privacy rakes and facing regular cycles of user outrage. Maybe Microsoft will stop ending up as a regular Privacy Disaster every few months.

Once again, a girl can dream. But at least in this instance, my dream is slightly more of a reality.

If you liked this post, consider liking, sharing, or leaving a content. Otherwise I’m just talking to my cats.

If you’re interested in a rather scathing rebuke of the state of EU policy which raises many of the same points I’ve brought up elsewhere (lack of consistency, clarity, etc.), I suggest checking out ‘The Future of European Competitiveness”, the 328-page beast that came out in September.

Article 1(2): “This Regulation shall apply to core platform services provided or offered by gatekeepers to business users established in the Union or end users established or located in the Union, irrespective of the place of establishment or residence of the gatekeepers and irrespective of the law otherwise applicable to the provision of service.”

The gatekeeper list can be modified by the European Commission due to the "durable" market position in some digital sectors and because they also meet certain criteria related to the number of users, their turnovers, or capitalisation.

You might observe that all but ByteDance and Booking.com are US-based. I’m pretty sure that the European Commission only really added Booking.com (which is based in the Netherlands) because they were getting shit on for not including any EU tech companies listed. Booking.com doesn’t even have a Designation Decision posted like the others, lol.

Article 3 DMA. A company is presumed to meet this threshold if they also meet certain exceedingly high economic and user thresholds— for example, making 7.5 billion EUR over a three year period within the EU, or having a market capitalization of at least 75 billion EUR, and having at least 45 million monthly active users located in the EU and at least 10,000 yearly business users in the EU, while maintaining an ‘entrenched and durable position’ in the market. It’s a VERY high standard.