Using Microsoft Recall? Welcome to Hell

Microsoft never reads my blog posts, but really they should, because Recall is a Privacy Disaster

In May 2024, Microsoft first announced that it would soon be releasing a new always-on, AI-enhanced, life-logging tool called Recall in May 2024. Unsurprisingly, I had some thoughts, none of them positive:

Now, I know that the gang in Redmond, WA don’t read this blog. But they did at least glance at Kevin Beaumont’s excellent and scathing security critiques on his blog, DoublePulsar. And I’m sure the initial onslaught of bad press didn’t help. That led the people responsible for Recall to take a beat and delay the launch a few times, in order to fix the most glaring security and privacy issues. I wrote a bit about some of the privacy-focused improvements here:

Last week, Microsoft announced that it was finally making the torment nexus Recall available to general audiences.

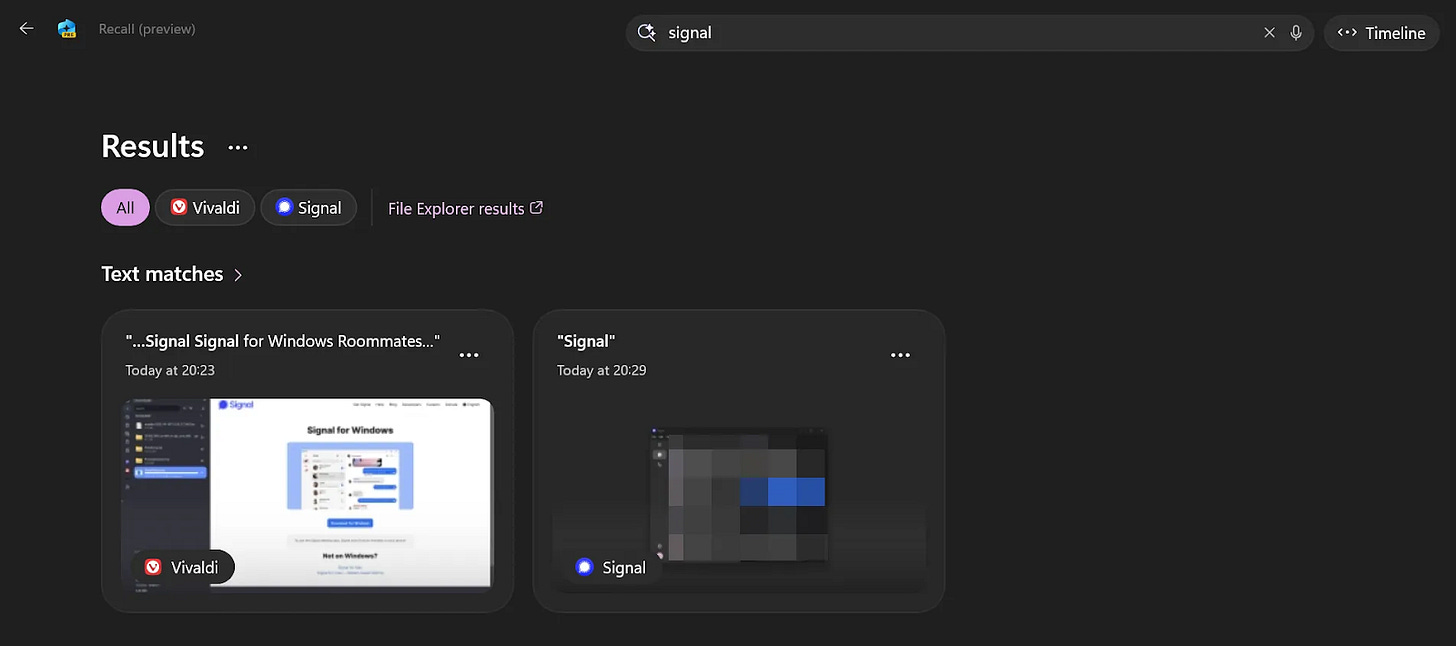

If you’re not familiar, Recall works by taking snapshots of a user's active screen every few seconds. These snapshots are organized into an explorable timeline, OCR’d and text-searchable, allowing users to use natural language to easily trace their activity back in time via the power of Microsoft’s onboard CoPilot AI. Additionally, a "Click to Do" feature allows users to interact with content within a snapshot, such as copying text or summarizing information.

Unfortunately, it’s clear that by releasing this solution in search of a problem, the Recall team didn’t learn the most important lesson of all: that some ideas are better left as science fiction. Seriously, has no one on the team ever read any Philip K. Dick???

And so, a year later, Recall is finally rolling out in general release, at least for Windows machines that meet certain hardware requirements. Kevin does a good job breaking the features down here, so for space purposes, I’ll just briefly summarize the privacy-focused aspects.

The Good:

Recall is now opt-in (as opposed to on by default) for the account holder. It’s still not great, and once it’s on, it’s easy to miss, but opt-in is still better.

The snapshots are now stored in an encrypted database. They were originally stored in an easily accessible cleartext SQL database.

Recall now includes a sensitive data filtering feature, so it won’t take screenshots that visibly show credit card information and government IDs and the like, but only if you’re using Microsoft’s Edge browser.

Copyrighted material protected by Digital Rights Management (DRM) or content viewed in InPrivate Browsing (but again, only in Edge) won’t be captured.

The Awful:

Unless the user is smart about it, it’s trivially easy to access and export Recall data once someone gains access to the device. Unless the user has enabled biometrics, all an attacker needs is the user’s Windows Hello PIN.

Recall’s sensitive data filtering feature is limited and inconsistent. Most types of sensitive information–health records, sensitive chat communications, confidential documents, and photos–won’t be detected by the software. And again, this only works on Edge.

Recall records everything at 30-second intervals, and stores it all unless the user manually deletes the snapshot(s), or the system runs out of hard drive space. Thinking about having a spicy Zoom chat with your partner? Recall will faithfully make a silent porno just for you! Plotting the overthrow of the US totalitarian state on Signal? Say hello to the CECOT gulags in El Salvador, because Recall will provide the authorities with a full record, even if you set messages to expire.

Credit: DoublePulsar

Using Recall at work? Recall makes exfiltration easy, and even Microsoft admits it.

I give it maybe six to a year before info stealers, nation states, DOGE, or scammers in India figure out a way to grab Recall data off user devices. Recall will make sextortion emails even easier.

And finally: Nobody else interacting with the user who set up Recall has any say on the matter, because they won’t know they’re being recorded by Recall.

Two Cases Show Why Recall is a Privacy Disaster

Microsoft touts Recall as a convenience and productivity tool—a way to fob off the complicated aspects of remembering things to your device. But before I get into how Recall will actually make the user’s life a living compliance hell, I need to start with some very important data protection lore: specifically two European Court of Justice (CJEU) decisions. Feel free to skip the summaries, if you’re a CJEU-stan like me.

The Lindqvist Decision (C-101/01)

In 1998, when the internet was still shiny and new, Mrs. Bodil Lindqvist, a well-meaning church worker and volunteer from the parish of Alseda in Sweden, created and published a website which included the names, telephone numbers, addresses, hobbies, jobs, and other ‘humorous’ biographical information about herself, her husband, and eighteen unknowing fellow parishioners. She even included sensitive health information: one of the members of the flock had an injured foot, and was taking some medical leave.

The Swedish authorities were not happy with Mrs. Lindqvist’s website at all, and fined her SEK 4,000 (approximately € 350) for violating the predecessor to the GDPR, the Data Protection Directive (DPD). A Swedish court determined that Mrs. Lindqvist had unlawfully processed personal data without having a basis to do so, and processed sensitive personal data (the foot injury) without consent.

Lindqvist appealed the fine, arguing that under the law, her processing wasn’t within the scope of the data protection laws, because she was merely using the data for purely personal, private uses, which is an exception under the data protection law. Here’s the relevant section of the Directive (which was carried over verbatim to the GDPR):

This Regulation does not apply to the processing of personal data... (c) by a natural person in the course of a purely personal or household activity.

Eventually, the CJEU weighed in and rejected Lindqvist’s argument. What constitutes ‘processing’ is broad under the law, the Court explained, but the exceptions to processing, including the household exemption, are quite narrow. ‘Purely personal or household activities’ extended to things like corresponding with friends, posting in a social media group, or keeping an address book. But the Court found that what Mrs. Lindqvist did–disclosing the personal data of her colleagues on the internet where anyone could see—fell outside of the scope of the exception. It was the context of that sharing, in a public forum, and not her intent, that made her a processor.

In 2007, Mr. Ryneš, increasingly worried about his family’s safety after a series of attacks against his family and home, installed a CCTV system on his property. However, the camera wasn’t limited to a view of his property—it also recorded activity along a public footpath and the entrance to a neighbor’s home. And so, on the night of October 6, 2007, when the camera faithfully recorded another attack, police were able to use that footage to identify the perpetrators and bring them to justice.

Unsurprisingly, the defendants sued, claiming that Mr. Ryneš’ use of the camera was unlawful under the Directive, and that he had collected their personal data without obtaining consent, or providing them with any notice or information. The central question before the Court of Justice was whether the operation of such a camera system which partially monitored a public space (the sidewalk, and the neighbor’s house), fell under the 'purely personal or household activity' exemption.

The CJEU determined that the operation of a camera system cannot be regarded as an activity which is a purely personal or household activity. Once again, the context, and not the subjective intent, mattered. Mr. Ryneš’ cameras weren’t just recording his own personal activities—they extended to anyone passing within the camera’s gaze. Even if Mr. Ryneš’ interests in processing the data were legitimate, his processing was still governed by the Directive.

Recall Users are Processors of Personal Data

The takeaway from these two cases, and the point of data protection laws like the GDPR, isn’t to turn every person who sends an email to a friend, shares a selfie with their WhatsApp group, or stores their family’s medical information on a cloud server, a controller. The point is to ensure protections are available to individuals when their personal data leaves the private sphere. In other words, when the context changes.

There have been cases since the Lindqvist and Ryneš decisions discussing the household exemption, but none have materially altered the importance of contextuality or the obligations that processing be ‘purely personal’ when it comes to the exemption. And this interpretation is important, not just for assessing Recall, but also with regard to other new technologies like spywearables and ever-encroaching uses of AI tools. Here’s why.

Nature of the Data Captured: Recall's operational design involves capturing a complete visual record of a user's screen activity. This inevitably includes troves of data that do not originate solely from the user or their household. Recall routinely captures and stores communications with and from third parties (via email, chat, private message boards, and social media), including work-related data if the device serves dual personal and professional purposes.

While Microsoft may reasonably argue that this already happens on a user’s machine anyway, the difference is both a matter of degree and ease of retrieval. By making Recall snapshots searchable (and using AI to add context to images), it means that every captured image is, as the name suggests, instantly ‘recallable’—turning a scattershot, impossible to differentiate pile of information into an easily searchable database.Scale and Systematicity: The continuous, automated nature of snapshot capture every few seconds represents a systematic form of data collection. This goes beyond incidental or selective ‘purely personal’ activities traditionally associated with the household exemption and identified under the law. Microsoft Recall represents continuous, systematic surveillance, albeit self-directed.

Just as the CCTV camera recording the public footpath extended surveillance beyond Mr. Ryneš’ home, Recall extends its near-permanent data capturing beyond the user's purely personal activities to everything the user interacts with online. This capture of data from beyond the user's private sphere aligns directly with the reasoning in Ryneš for finding the household exemption inapplicable.Context Matters: Recall captures interactions outside the context with which it was shared in the first place, echoing one of the concerns addressed by the Court in Lindqvist. Without asking first and obtaining consent from the individuals whose data she collected and shared, Mrs. Lindqvist violated their implicit autonomy and choice. She made what was private, public.

Imagine the implications: All those short-lived Signal chats, ephemeral meetings over Zoom, fleeting Snapchat sexts, or ill-advised tweets posted in anger, will now live on for months, years, or decades, recallable in an instant. And while Microsoft doesn’t make Recall data public (at least for now), give it a few months—someone will get there eventually. Recall represents a wet dream for attackers, insiders, authoritarian governments, and law enforcement. It’s yet another tool that domestic abusers can use against their victims and a new weapon that parents can employ against children they suspect of being ‘different.’ Like so many Microsoft processes, it runs silently in the background, and users may not even be aware that it’s recording.Blurring of Personal and Professional Use: Many organizations now have Bring-Your-Own-Device policies, blurring the lines between systems that belong to the user versus the organization. That necessarily means a mix of personal and professional tasks can spill over into Recall’s memory, where it captures professional emails, work documents, business communications, and interactions with colleagues or clients. Such processing clearly falls outside any definition of a 'purely personal or household' activity. Even activities related to volunteering, participation in clubs, or engagement in online communities are arguably outside of the scope described by the CJEU (though other exceptions may apply).

More Bad News: Recall Users Are Probably Also Controllers

Okay, so Recall makes you a processor. So what?

Once someone is within the scope of data protection laws like the GDPR, they’re also subject to obligations under the law. The GDPR defines a number of different roles for entities that process personal data, including controllers and processors. Individual Recall users will most likely be seen as controllers of personal data, because they decide the ‘why and how,’ or as the GDPR says, the 'purposes and means' of processing’ personal data. Microsoft, by comparison, will be seen as a processor—because they merely designed the tool and it only does what the user asks it to.

For example, it’s the user who decides whether to enable the tool and why they want it enabled (their purpose, or ‘why’), and what activities they engage in concerning personal data (aka, ‘process’) while it is active, which directly determines the scope of data captured. The user also controls the essential means (or ‘how’) by deciding to use Recall for these purposes and managing its operation (activation, pausing, deletion).

And boy, are there a lot of obligations for controllers under the GDPR!

Here are just a few:

Adhere to Data Protection Principles (Article 5): Recall users must ensure that their processing is lawful, fair, and transparent; for specified, explicit, and legitimate purposes (purpose limitation); adequate, relevant, and limited to what is necessary (data minimisation); accurate; stored no longer than necessary (storage limitation); and processed securely (integrity and confidentiality).

Have a Lawful Basis (Article 6 & 9): Recall users must identify and document a valid legal basis (or reason) for processing data and a separate basis for processing sensitive data (like health records, details about a person’s sex life, sexual orientation, or religious and political beliefs).

Transparency and Information Duties (Articles 12-14): Users will need to provide clear and comprehensive information to data subjects about the processing of their data. That means, privacy notices!

Data Subject Rights (Articles 15-22): Recall users will need to establish procedures to receive and respond to requests from data subjects exercising their rights, including the right of access, rectification, erasure, restriction of processing, and the right to object.

Data Security (Article 32): Recall users must Implement appropriate security measures to ensure a level of security appropriate to the risk, including measures like encryption, access control, and resilience of systems. As I mentioned above, that four-digit PIN likely isn’t going to be enough.

Data Breach Notification (Articles 33-34): If a user gets hacked, or accidentally let someone else peer into all those snapshots, and they post the content online, the user will be responsible for notifying the relevant supervisory authorit(ies) and potentially affected individuals.

Accountability (Article 5(2) & 24): Should a regulator come a’knocking, users will need to show that they’re doing all of these things (and more).

And there are consequences for not doing things right. Here, I’m not just talking about fines. Recall users are opening themselves up to data subject requests and complaints by aggrieved individuals, investigations by data protection authorities, civil liability, including for non-material damage, and in some countries like Ireland, potential criminal penalties. For what it’s worth, both Spain and Germany’s regulators are very proactive about going after individuals who violate the data protection laws. Even though the fines may be small, the stress and time can be overwhelming.

Plus, there’s the whole fact that if someone finds out you’ve been storing every sensitive conversation, Snapchat sexy pic, or deeply embarrassing video confession, they’re going to feel violated. You’ve stripped them of their choice and their autonomy. Ephemeral communications die when you add Recall to the mix.

And for all my US friends and commenters, don’t think you’re immune just because you’re outside of the EU/UK/EEA. The odds are high that someone you’re interacting with online—a friend, family member, random Reddit stranger, colleague, or Twitter shitposter, calls Europe their home. And just like that, potentially millions of individuals using Copilot+ PCs anywhere in the world could become data controllers under EU law simply by enabling a built-in operating system feature, without any explicit awareness of this legal status change or the significant responsibilities it entails.

New Fresh Hells Await Organizations

Yesterday, on LinkedIn, one beer into this article, Tash Whitaker and Val Dobrushkin independently got me thinking of a new fresh hell: if organizations think data subject access requests (DSARs) are a nightmare now, just imagine what a DSAR will look like when there’s a surveillance tool indiscriminately recording every employee’s screen interactions at 30-second intervals all the time, with no defined retention (aside from 'ran out of hard drive space’).

Dealing with data subject requests can already be difficult and complex affairs, especially when it comes to requests made by disgruntled employees, pissed off customers, or snubbed job applicants. Frequently, the data organizations maintain can be extremely sensitive, voluminous, and in some cases, highly damaging to the organization. Filing a subject access request also represents an effective backdoor discovery tool to find out what the organization may know prior to bringing a lawsuit.

With Recall enabled, SARs will extend well beyond emails, HR files, and internal correspondence. Now, everything from web searches and background research, purged chat messages and documents, internal notes, draft emails, and messages that were never meant to see the light of day may be in scope. No matter how embarrassing, potentially incriminating, or uncomfortable these documents are, a data subject is still entitled to a complete, faithful, and intelligible copy of the data that relates to, or is about them (FF v.Österreichische Datenschutzbehörde, C-487/21). And while exceptions exist under the law, like the household exemption, they tend to be limited, and I doubt the EU is likely to include a “Microsoft Recall” exemption any time in the future.

Now, someone will have the thankless task of searching for all of that, across individual devices, because this is data that will absolutely be in scope of a rights request and may be ever-so-slightly different across different machines. Just imagine the volume of records! And I'm not even talking about all the images captured of every Teams/Zoom meeting, which would also be in scope. Having done a fair number of complex, messy DSARs in my day, It honestly makes me hyperventilate just thinking about it.

Finally, here’s a fun question for the lawyers to ponder: Is a draft version of a privileged document still privileged before it gets blessed by an attorney?

Here’s another: Thinking about getting divorced and worried it might be contentious? You might want to check if Recall is recording …

Anyway, happy Friday, y’all. Welcome to hell.

Here’s a cat to brighten your weekend. Please don’t use ChatGPT to find out where I live.